Dec 29, 2025 · 9 min read

What Does Information Theory Say About Designing Agentic Systems?

Shizhe He, Avanika Narayan, Ishan S. Khare, Scott W. Linderman, Chris Ré, Dan Biderman

TL;DR Many contemporary agentic systems exhibit a clear pattern: larger models interact with the user and orchestrate smaller models that directly interface with the data. In “Deep Research” systems (Google, Anthropic), smaller worker models analyze targeted search results and provide summaries to a larger orchestrator model, which synthesizes a final research report. This separation of control and data plane is also evident in Claude Code and relatives (OpenCode), but it is unclear where scaling actually pays off. This compression-prediction structure isn’t new, an information-theoretic model helps us derive design principles that guide compute spending. Looking at the information actually communicated between the models showed that investing in compressors for relatively cheap mitigates the need for expensive frontier predictors.

Picking the "right" workers is no easy task for Gru.

The Art of Designing Agentic Systems

Agentic systems are everywhere now—multiple language model agents (often running in parallel) help you debug your code, summarize a 200-page document, or crawl the web for research papers.

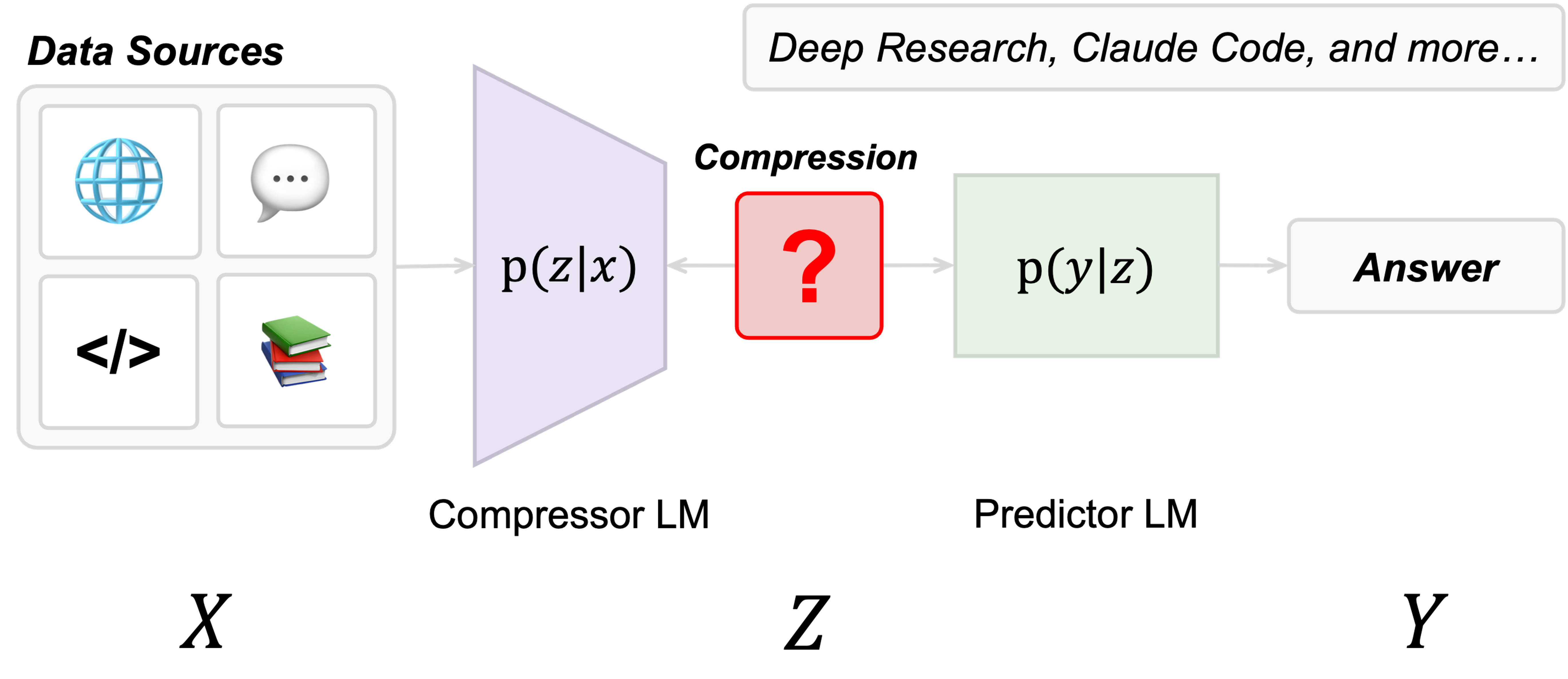

Modern workflows routinely challenge the long-context capabilities of even the largest frontier models, resulting in a decline in model performance referred to as context rot. Agentic systems split tasks across two models working in tandem. First, a larger orchestrator breaks a user query into focused sub-queries. Smaller workers go through large amounts of data to extract information that matters most for each query. Then, the orchestrator builds on those findings, either weaving them together into coherent outputs or sending out another round of queries. We observe that in these worker-orchestrator systems, the small model acts as a compressor—it reads the full context (e.g. search results) and provides a compressed view to the larger predictor model.

But here’s the problem: we still don’t have a principled understanding of when to scale the compressor or the predictor. If we knew which component of a compression-prediction system actually drives performance, we could make surgical changes to the system and avoid paying for the wrong things.

Thus, we ask:

Which design decisions in a compression–prediction system are worth paying for?

Not All Compute is Equal

We want to talk about where to spend compute, but not all compute is equal.

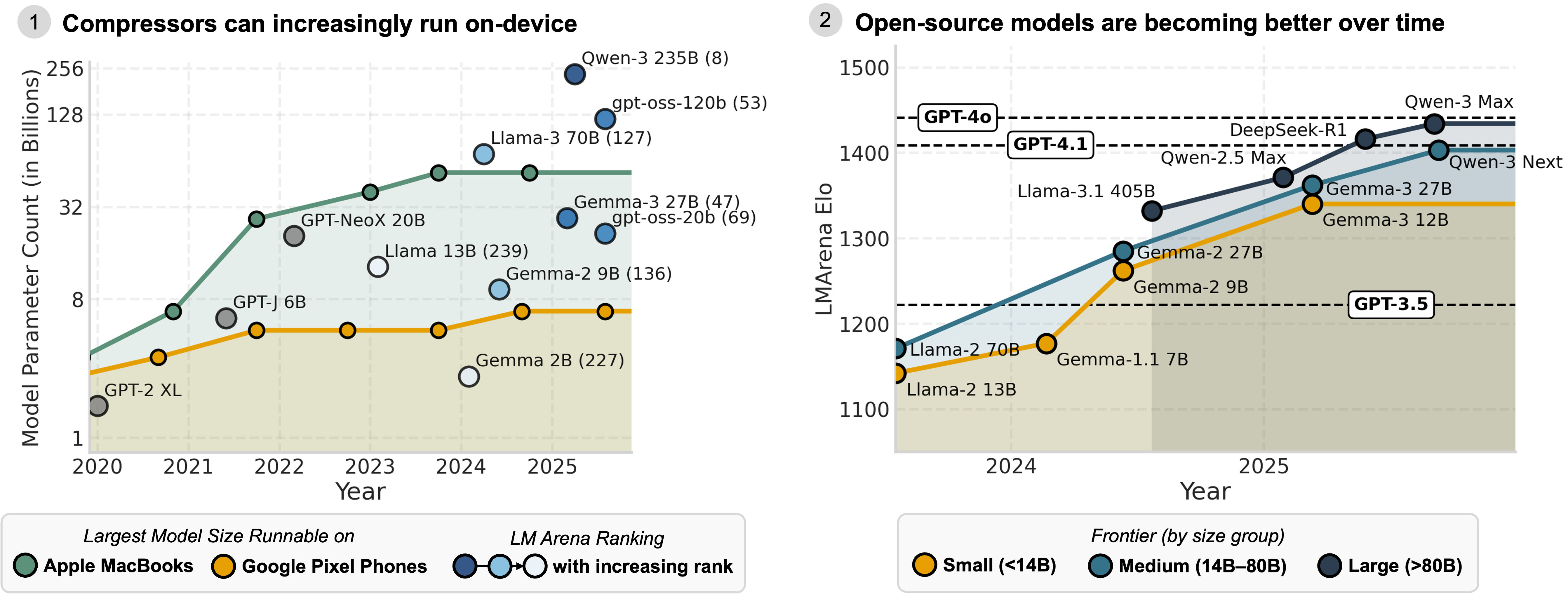

Thanks to fast-improving consumer hardware, and increasingly capable small models, we forecast a world where near-SOTA compressors can run locally on laptops and phones in the coming years. These tailwinds point to an interesting future for distributed, hybrid agentic computing, which we’ve explored in our previous blogs (Minions, Intelligence per Watt): large cloud models orchestrate workers that run on user devices.

Once you own the device, you can simply scale local models to the largest size the hardware can support, for free. Keeping computation local keeps data local, improving privacy and reducing the networking overhead required for cloud inference.

Scale Smarter, not (always) Bigger

As compression-prediction systems grow larger and end-to-end sweeps are no longer feasible, there must be a smarter way than simply making every model bigger. We have to scale smarter—deciding where to spend compute and what information actually flows between models.

Through large-scale experiments, we’ve distilled a few key principles for scaling compression-prediction systems efficiently:

- Compressors can be scaled at a sublinear computational cost — Larger compressors yield higher downstream QA accuracy, and output fewer tokens, so the total cost grows slowly.

- Spend on local compressors to save on remote predictors — It’s cheaper and more effective to scale compressors that can run on-device than to burn budget on ever-bigger predictors on the cloud.

- Optimize for information density — More intelligent models express more task-relevant information in fewer tokens; we can measure higher compression quality in their communication.

- Compressor model family > compressor size > predictor size — Compressor model family is the most important knob to turn. Matching families doesn’t matter; some families are just better than others.

In the rest of this post, we’ll unpack how we arrived at these principles. We’ll start from our information-theoretic perspective and trace empirical evidence across different domains and tasks.

An Information-Theoretic Problem in Disguise

Current compression-prediction systems are evaluated only on end-to-end performance on specific task-based evaluations. This conflates two distinct failure modes: information lost during compression, and information retained but poorly synthesized by the predictor. We turn to information theory to unpack what information is actually communicated between the models, and do so in a way that is general across tasks and domains.

Compression followed by downstream prediction is a classical setting in information theory. The compressor acts as a noisy channel—exactly how we view the worker models. You can actually measure compression efficacy—that is, how much signal survives the compression—between X and Z using mutual information (MI). You are able to evaluate the compression output independently from downstream performance, which allows us to come up with generalizable system design principles.

Performance Lies with the Compressor

When your compression-prediction system struggles, should you invest in a larger compressor or predictor?

To find out, we scaled both models across five realistic tasks that require extracting domain-specific information out of long context documents:

- Medical QA on patient records over time (LongHealth)

- Financial analysis of 100-page financial filings (FinanceBench)

- Question answering on academic research papers (QASPER)

- Question answering over long web pages (FineWeb)

- Information recall across multi-session chats (WildChat)

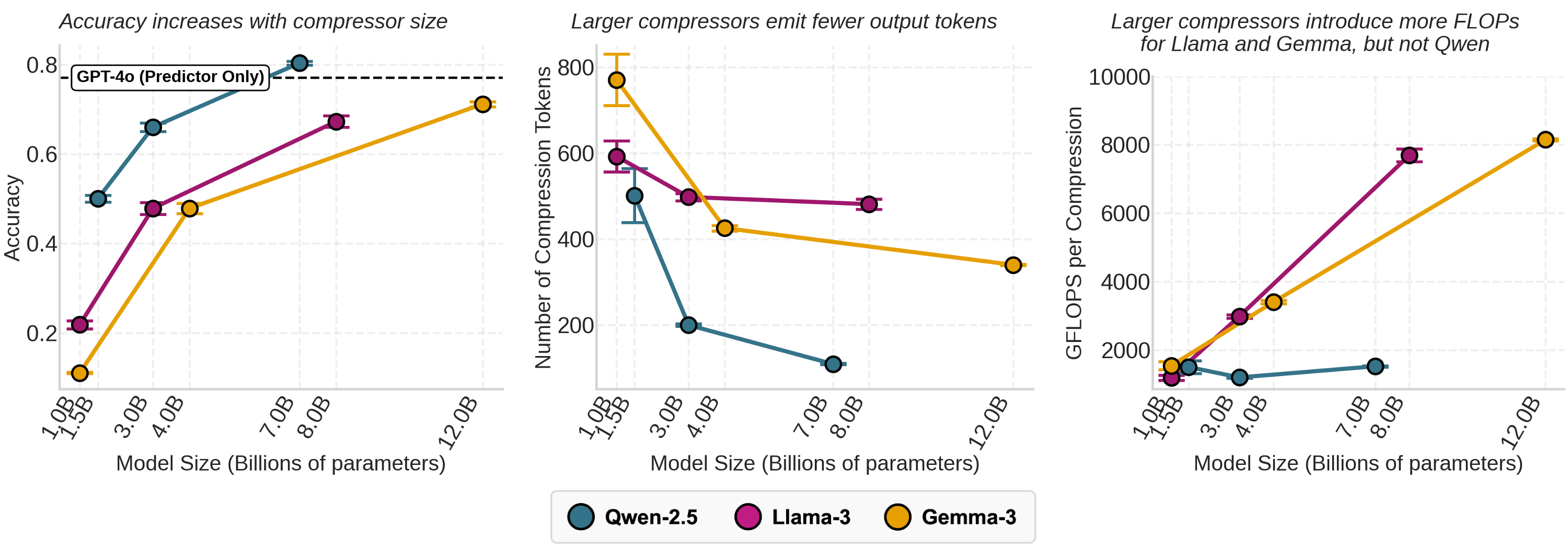

Scaling compressors. We fix the predictor (GPT-4o) and scale the compressor from 1–1.5B up to 7–12B. We observe interesting scaling trends:

- Downstream performance — Larger compressors—as expected—improve downstream performance.

- Compression length — Larger compressors produce outputs that are more concise (up to 4.6x !).

- Compression compute cost — Because larger compressors generate fewer tokens, the number of math operations that occur with each compression (FLOPs-per-generation) scales sublinearly with model size; strikingly, Qwen-2.5 compressors scale almost “for free” (just 1.3% extra FLOPs-per-generation!).

And this holds even when we explicitly ask the compressor to output a fixed number of sentences!

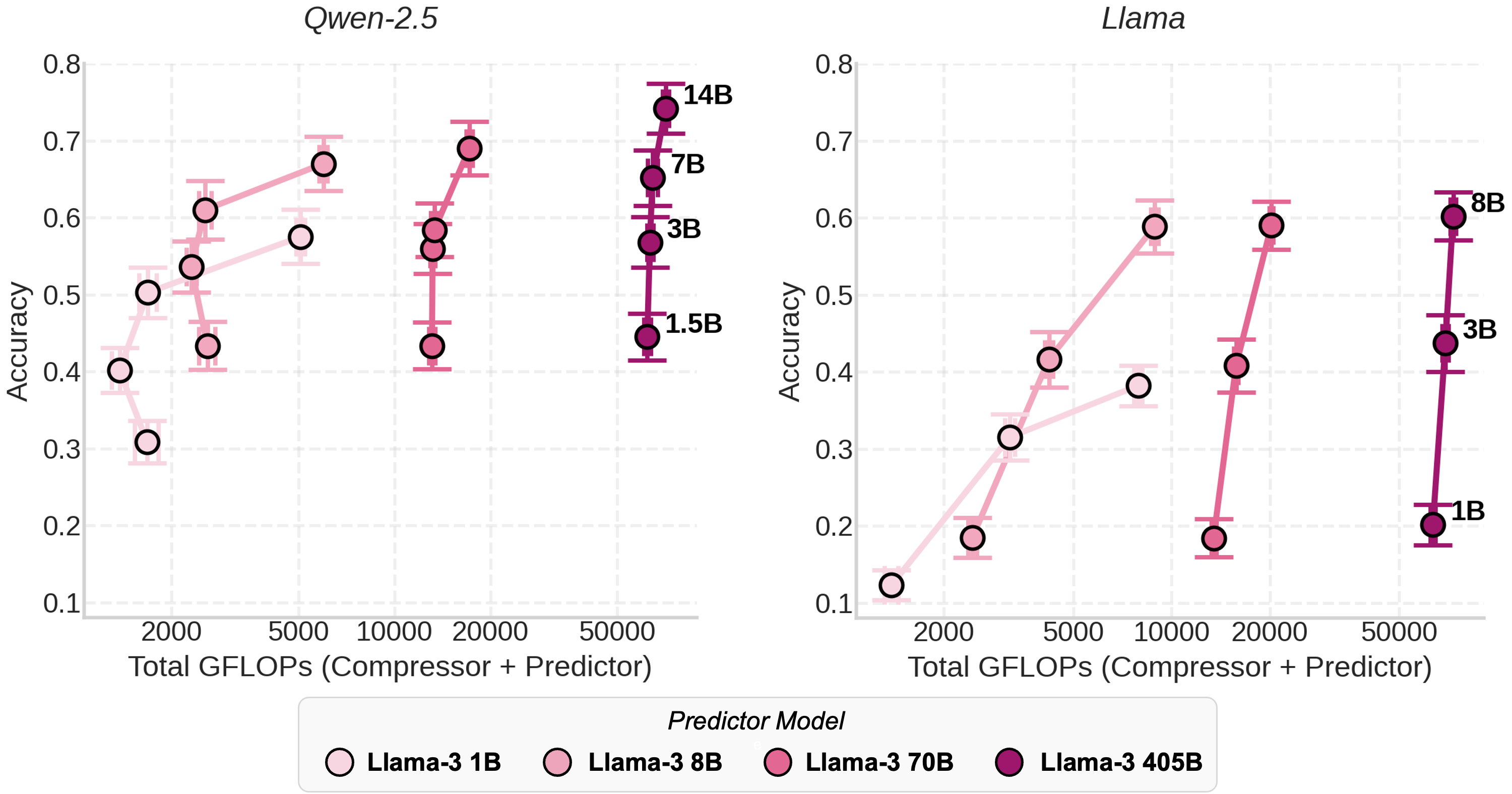

Scaling predictors. Now flip it: we fix the compressor, scale the predictor from 1B up to 405B. The accuracy curve flattens out quickly once a baseline predictor capacity is reached (8B–70B). While scaling a Qwen-2.5 compressor from 1B to 7B improves accuracy by 60%, scaling the predictor from 70B to 405B adds only 12%. No matter how big the predictor is, it cannot recover information that was never provided by the compressor.

Looking at total compute makes this contrast even starker. Scaling predictors means burning FLOPs on cloud APIs for each query, while scaling compressors gives you steeper gains at nearly flat cost—at least up to 7–8B.

Mutual Information: the Perplexity for Agentic Communication

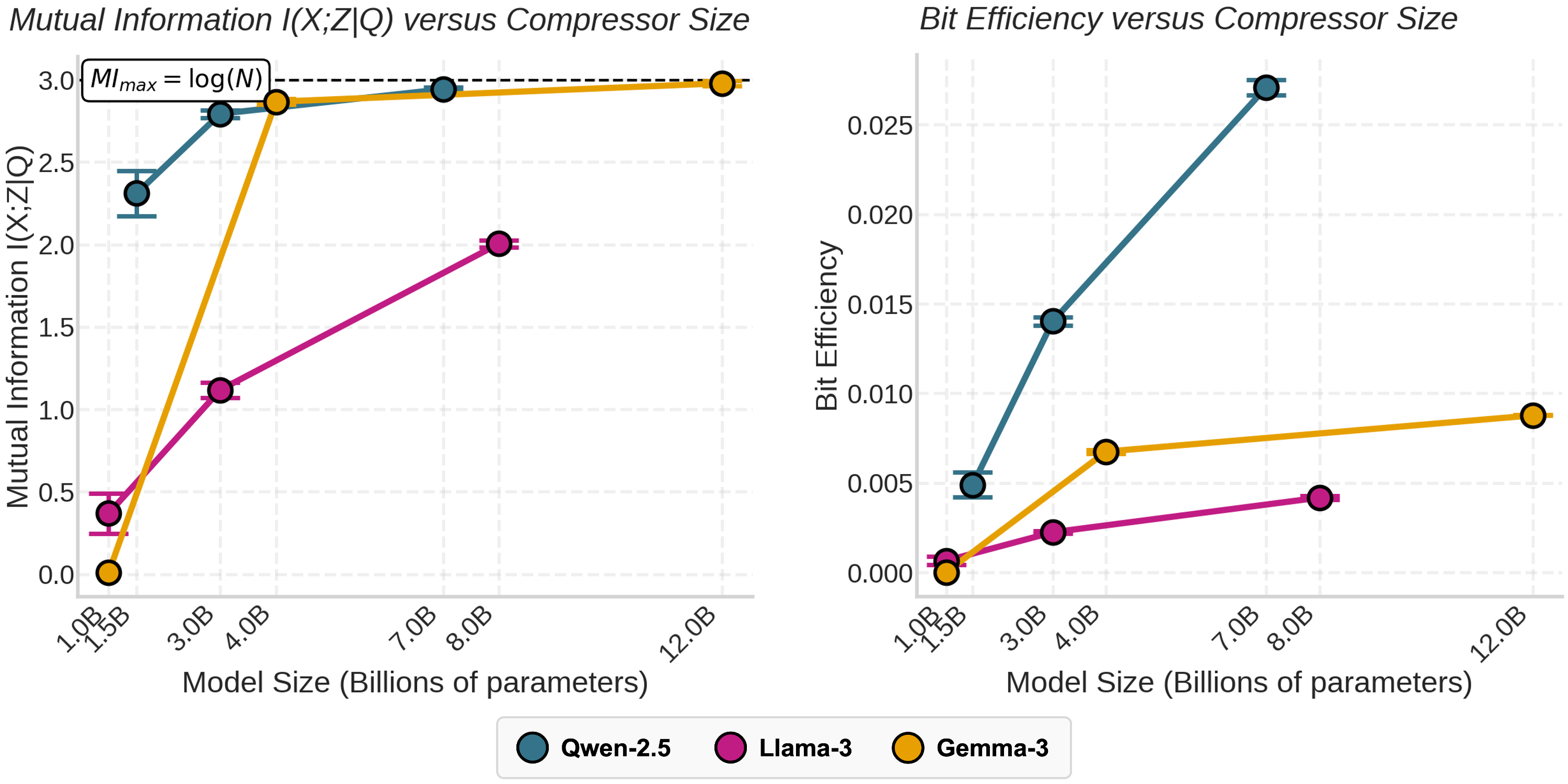

Now that we’ve seen that compression capacity is crucial to downstream task performance, we ask: what sets one compressor apart from another? A better compressor is one that communicates as much task-relevant information as possible in as few tokens as possible.

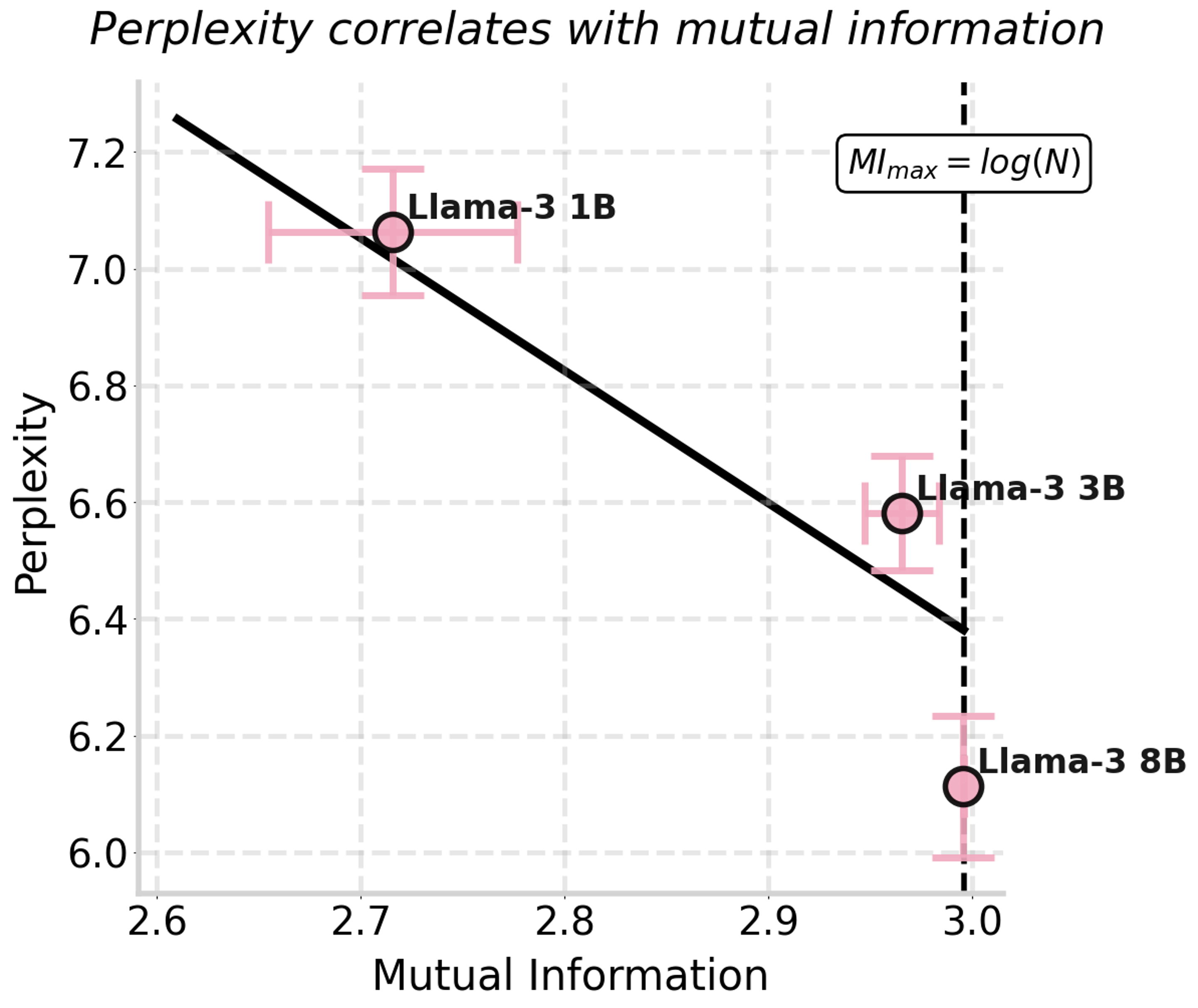

We turn to mutual information to directly measure the information passed from compressor to predictor. Just as perplexity is an effective indicator for model performance, mutual information can serve as a task-agnostic indicator of compression quality.

Our experiments confirm this hypothesis—mutual information correlates with both downstream accuracy (after sampling) and perplexity. It is an indicator for system performance that can be measured without actually running the prediction step.

More importantly, larger models produce compressions that retain more mutual information—up to 5.4x more! Since larger compressors are also more concise, they don’t only communicate more information, but do it more efficiently per token.

Making Deep Research go Brrrrrrrr

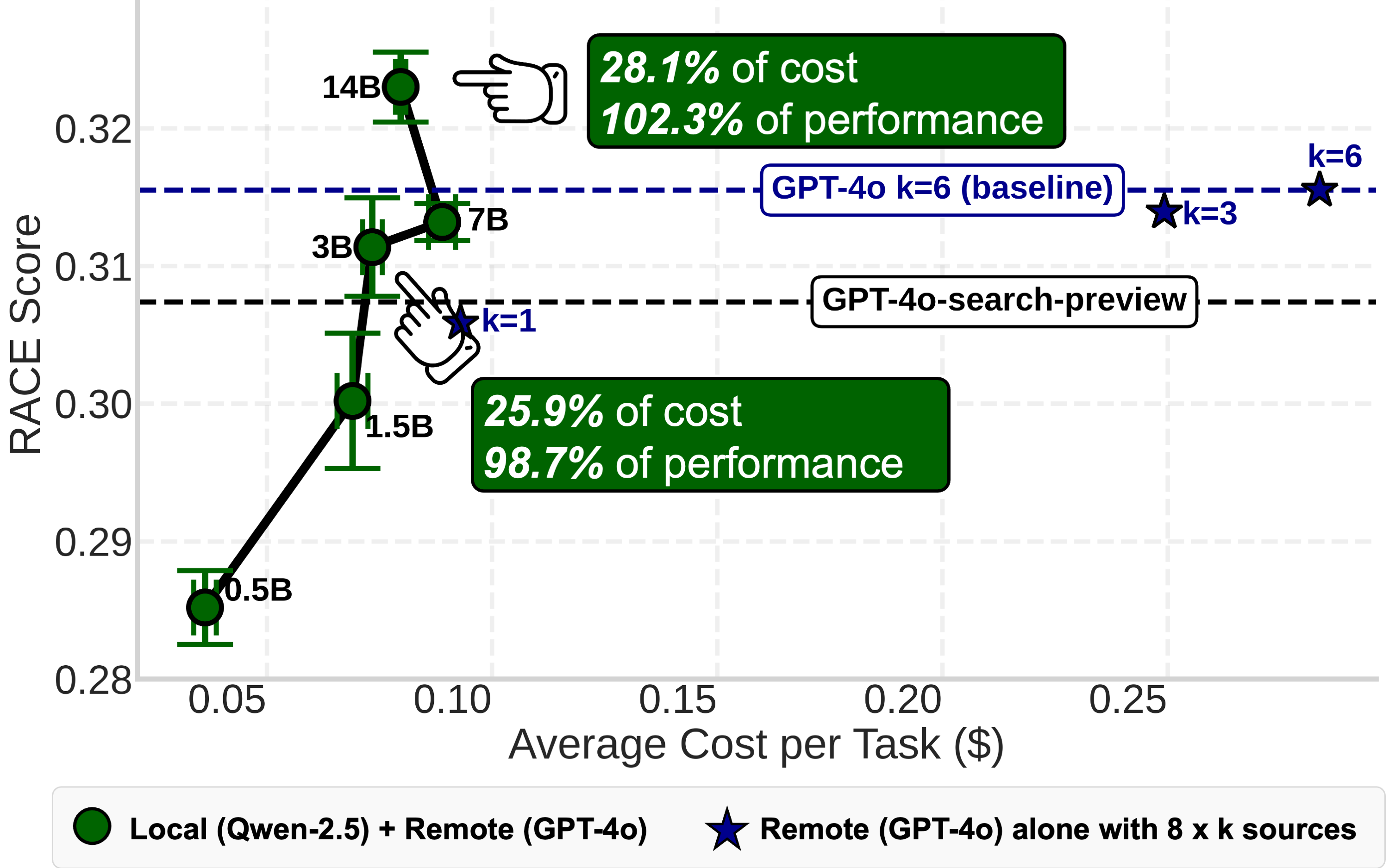

We put these lessons to the test in something that looks closer to a Deep Research system. On DeepResearch Bench, we scaled compute into larger compressors instead of scaling predictors. With compressors that could run locally, we were able to achieve 102% of frontier-LM only performance at only 28% of the cost.

Information Theory Paves a Path Forward

With our information-theoretic framing of compression-prediction systems, we take a first step towards a more principled approach to designing multi-model workflows. As compression-prediction systems become more and more complex, and as small models increasingly run on-device, the future won’t be about ever-larger models hosted on the cloud, but about more information exchanged between smaller models. Mutual information will become a standard metric of intelligence in compression-prediction systems, embedded into the training, routing, and evaluation of workflows.

What’s next? We see a number of opportunities to explore. Mutual information remains difficult to estimate for LMs in practice. Models can be jointly trained to optimize for compressor-predictor communication, and alternative communication avenues beyond natural language can be built (communicating features, not text). Information-theoretic concepts could guide routing decisions in complex compression-prediction systems.

Additional Resources

Acknowledgements

We are incredibly grateful to Modal and Together AI for providing valuable compute resources and credits. We thank Simran Arora, Yasa Baig, Kelly Buchanan, Sabri Eyuboglu, Neel Guha, Simon Guo, Jerry Liu, Jon Saad-Falcon, Frederic Sala, Ravid Shwartz-Ziv for providing invaluable feedback during the writing of the paper.