Nov 11, 2025 · 15 min read

Intelligence Per Watt: A Study of Local Intelligence Efficiency

Jon Saad-Falcon*, Avanika Narayan*, John Hennessy, Azalia Mirhoseini, Chris Ré

TL;DR:

AI demand is growing exponentially, creating unprecedented pressure on data center infrastructure. While data centers dominate AI workloads due to superior compute density and efficiency, they face scaling constraints: years-long construction timelines, massive capital requirements, and energy grid limitations.

History suggests an alternative path forward. From 1946-2009, computing efficiency (performance-per-watt) doubled every 1.5 years (Koomey et al.), enabling a redistribution of computing workloads from data center mainframes to personal computers (PCs). Critically, this transition didn't occur because PCs surpassed mainframes in raw performance: efficiency improvements enabled computing capable of meeting end-user needs within the power constraints of personal devices.

We are at a similar inflection point. Local language models (LMs), with ≤20B active parameters, are surprisingly capable, and local accelerators (e.g., M4 Max with 128GB unified memory) run LMs at interactive latencies. Just as compute efficiency defined the transition to personal computing, we propose that intelligence efficiency defines the transition to local inference. To this end, we introduce intelligence per watt (IPW): task accuracy per unit of power. IPW is a unified metric for measuring intelligence efficiency, capturing both the intelligence delivered (capabilities) and power required (efficiency).

We evaluate the current state and trajectory of local inference efficiency through two questions: (1) Are local LMs capable of accurately servicing a meaningful portion of today’s workloads? and (2) Given local power budgets, how efficiently do local accelerators convert watts into intelligence? We conduct a large-scale study across real-world single-turn chat and reasoning tasks, revealing:

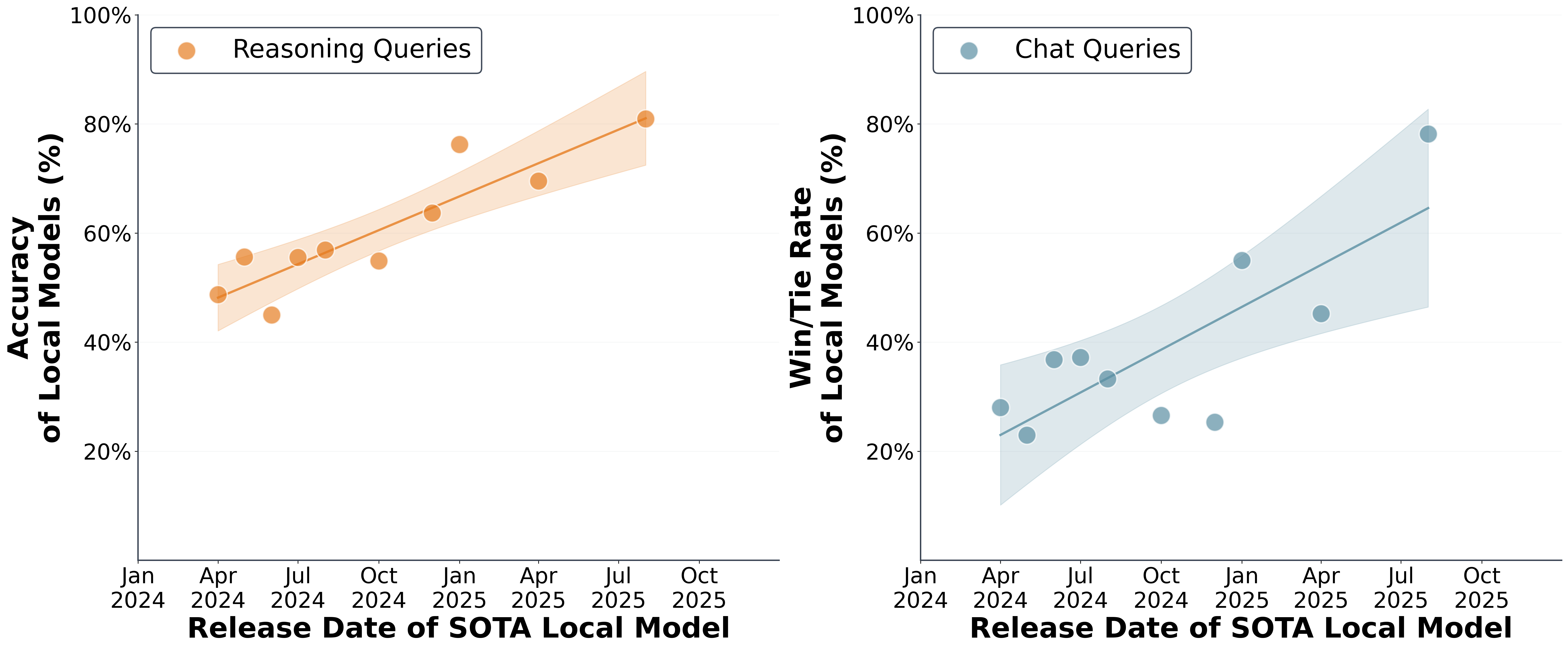

- Local LMs are capable and improving rapidly: Local LMs can accurately respond to 88.7% of single-turn chat and reasoning queries, with accuracy improving 3.1× from 2023-2025.

- Local accelerator efficiency has room for improvement: Inference on a local accelerator (Qwen3-32B on an M4 Max) demonstrates 1.5x lower intelligence-per-watt vs. inference of the same local LM on an enterprise grade accelerator (i.e., NVIDIA B200).

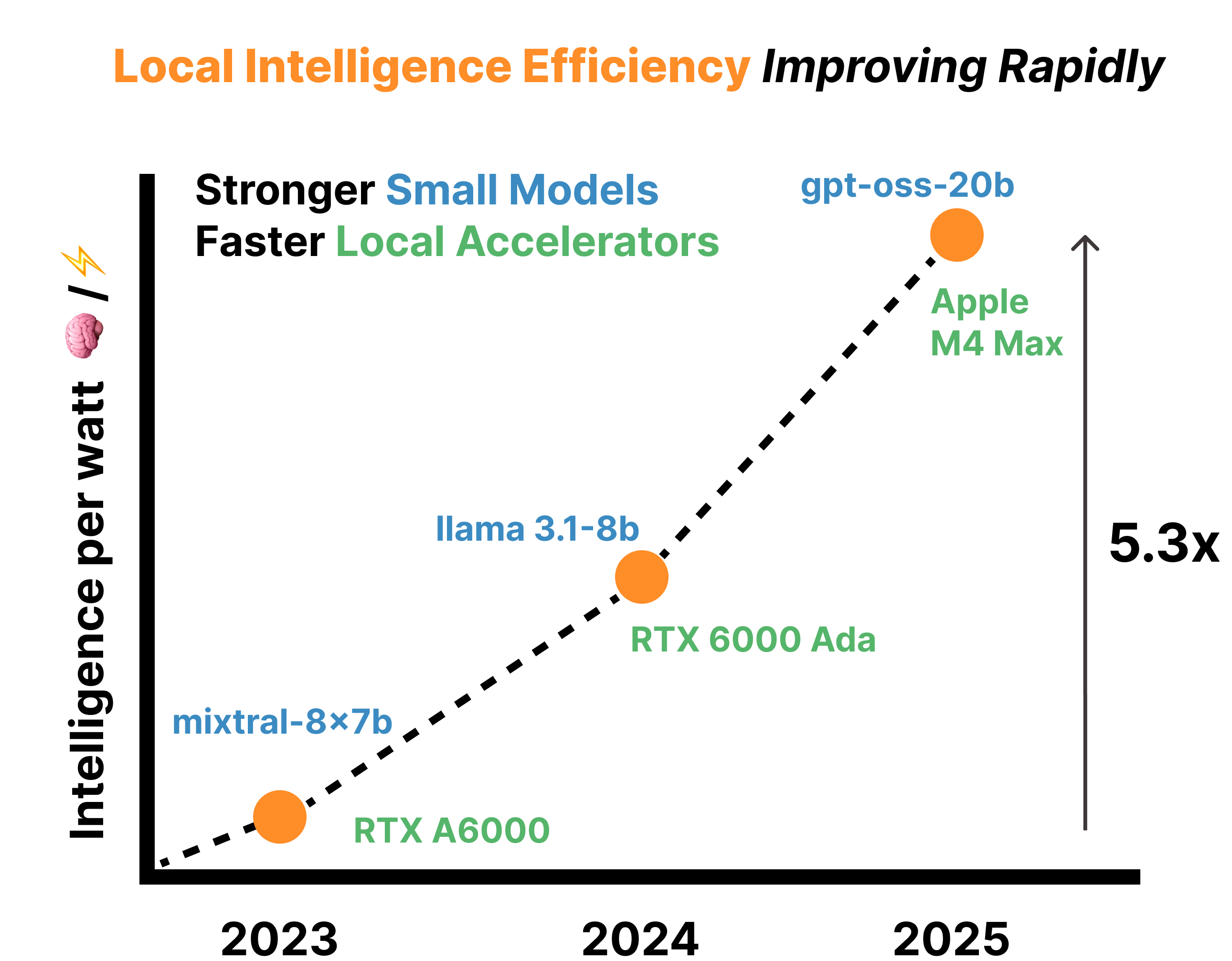

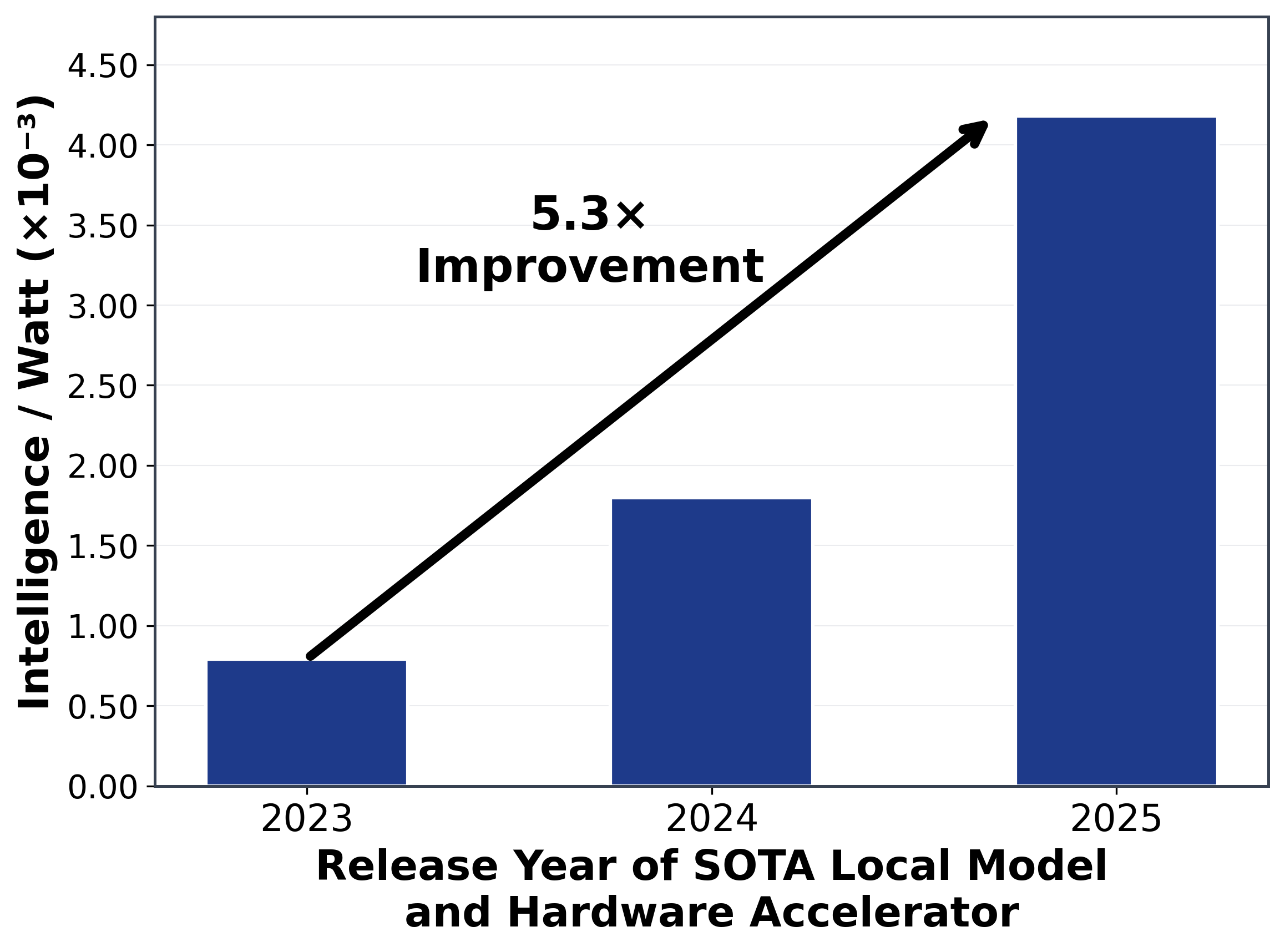

- Local intelligence efficiency is improving 5.3x from 2023 to 2025: 3.1x from model improvements (thanks to advances in model architectures, pretraining, post-training, and distillation) and 1.7x from accelerator improvements.

Call to Action: As AI demand grows exponentially, we must find better approaches to turn energy into intelligence. We envision a world where intelligence is everywhere and in every device: in earbuds providing instant translation, in glasses offering real-time visual assistance, and in pocket assistants solving graduate-level problems. By prioritizing intelligence-per-watt in both model design and hardware acceleration, we can bring powerful AI to billions of edge devices and make intelligence truly ubiquitous. We release a profiling harness to enable systematic benchmarking of intelligence per watt as local LMs and accelerators evolve.

🏢 The Mainframe Era — Demand is exploding faster than infrastructure can scale

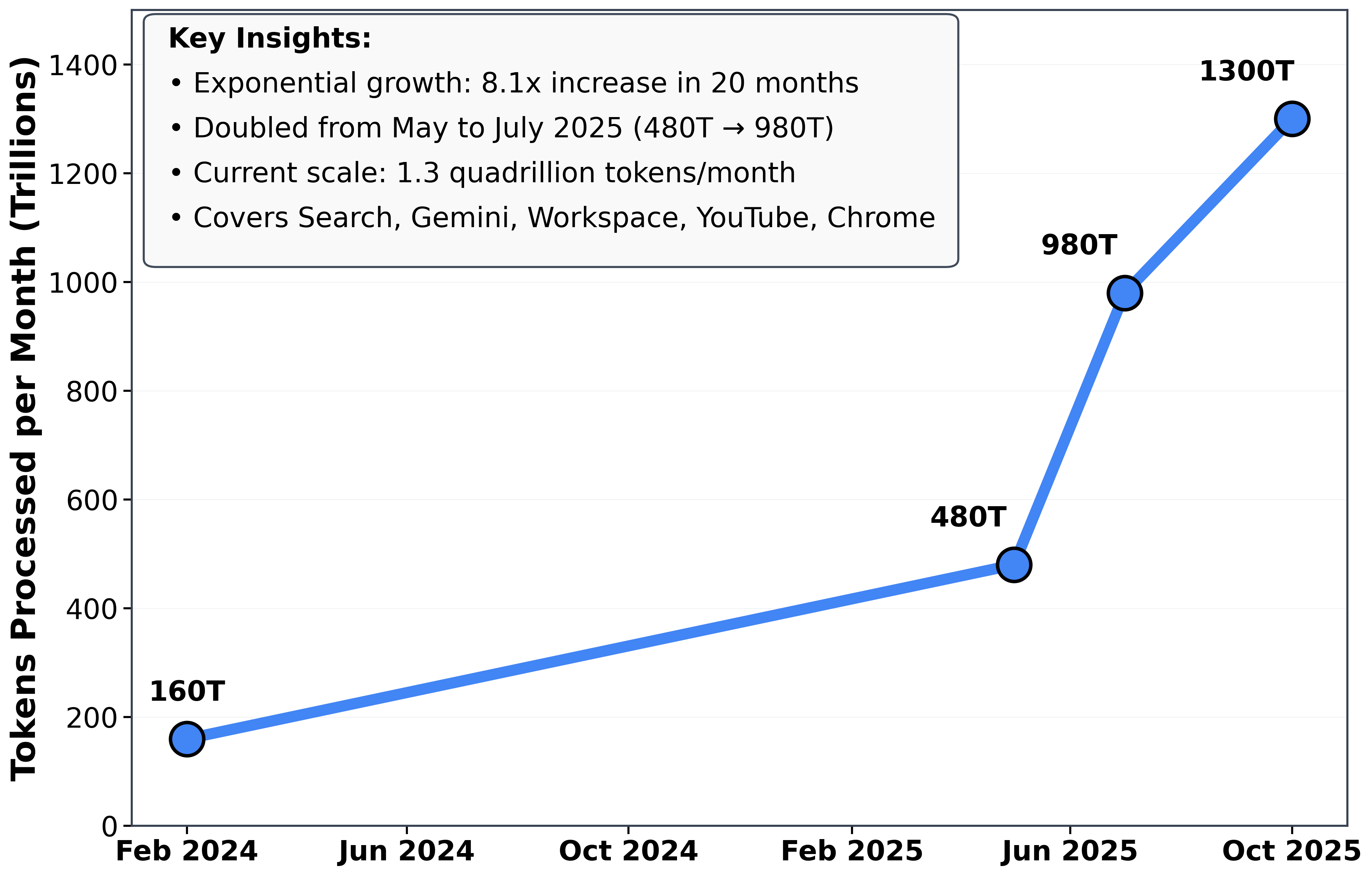

Demand is surging, with Google Cloud reporting a 1300× increase in monthly token processing (see Figure 1), and NVIDIA noting a 10× year-over-year increase. Today, most AI queries are serviced by monolithic inference infrastructure: massive, centralized data centers with frontier LMs processing most queries, much like the time-sharing mainframes of the 1960s (h/t Andrej Karpathy).

To keep up with this exploding demand, the industry is calling for unprecedented infrastructure buildouts spanning GPUs, energy projects and massive data center buildouts (Sam wants 250GW 😱). Frontier labs are right to build large models: the path to AGI demands it. But we're using that same infrastructure to answer "write me an email" and "summarize this document.”

Internal ChatGPT telemetry data shows 77% of requests are practical guidance, information seeking, or writing — tasks that don't require frontier capabilities. Put simply, user demand ≠ frontier LM capabilities. This raises the question of whether these simpler tasks can be served by smaller, cheaper models locally.

While centralized inference offers advantages like high-throughput batching and consistent utilization*,* offloading lower-complexity tasks to local compute could complement centralized systems preserving frontier infrastructure for tasks that truly demand them.

💻 Dawn of the PC AI Era — Local inference as a path to redistribute compute

Excitingly, we're seeing the emergence of two parallel trends across the model and hardware layers that allow for the possibility of redistributing AI workloads to local resources.

Better small models: Local LMs (≤20B active parameters) such as Qwen3 4B-14B, gpt-oss-20b, Gemma3 4B-12B, and IBM Granite 4.0 1B-7B are improving quickly, taking on an expanding range of tasks once limited to frontier‑scale models (Kumar et al., IBM, Yang et. al. (2025), Deepak et. al.,).

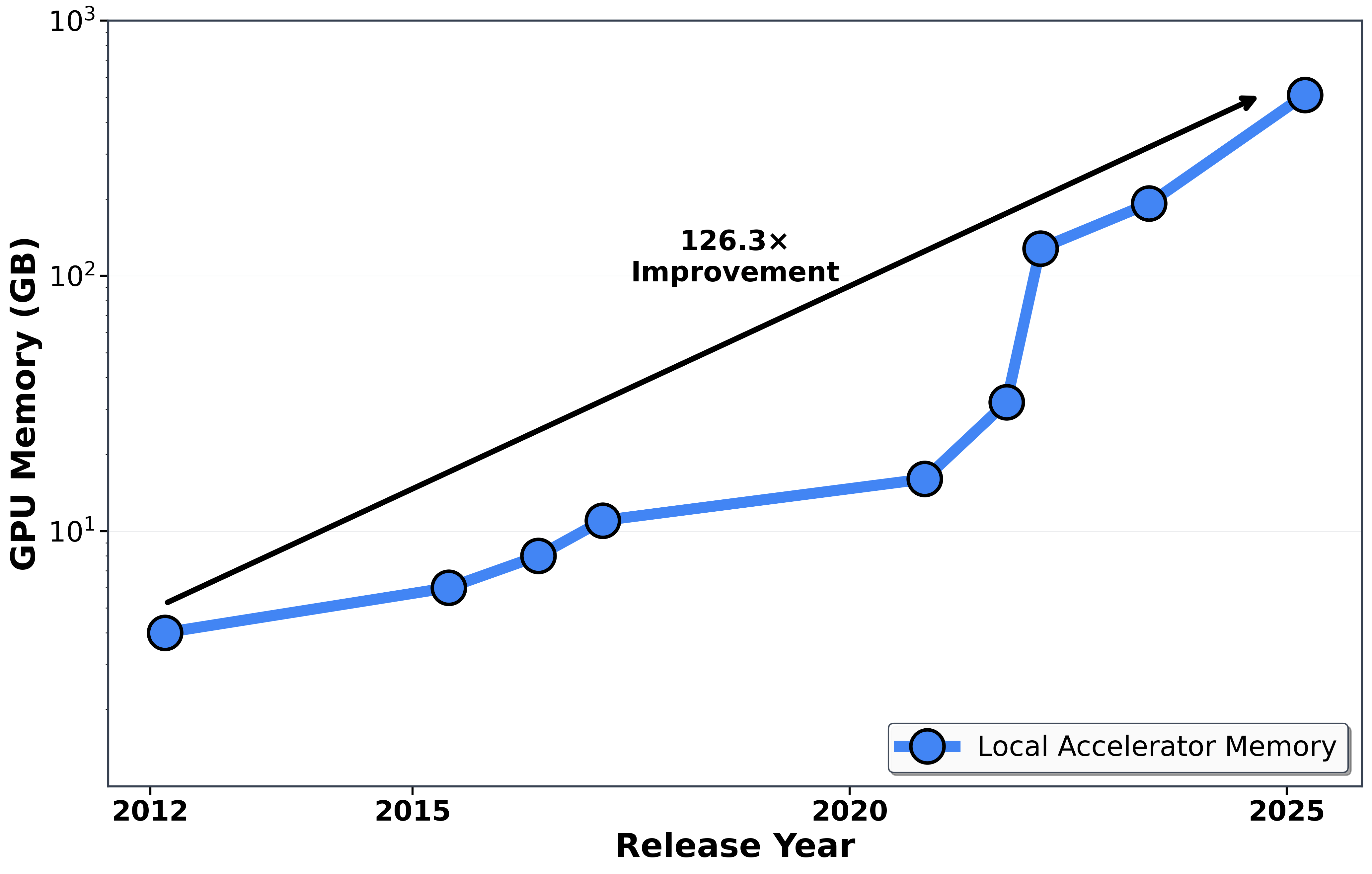

More powerful local accelerators: Local accelerators — from smartphone NPUs to laptop accelerators (Apple M4) to desktop GPUs (NVIDIA DGX Spark) — now run models once confined to data centers (see Figure 2). Consumer laptops with 128GB unified memory can run models approaching 200B parameters , desktop GPUs enable 200B parameter models with quantization, and smartphone NPUs run 7B models at over 8 tokens/second.

This raises a critical question: What role can local inference play in redistributing inference demand?

🧠 / ⚡ Intelligence-per-watt: measuring intelligence efficiency

We answer this by measuring how effectively inference systems convert energy into useful computation, examining two key dimensions:

- Capability: What % of today's single-turn chat and reasoning LLM queries can local LMs answer correctly?

- Efficiency: How much useful compute (i.e., accurate inference) do we get per watt when running local LMs on local hardware? Energy efficiency is paramount for local inference given constrained power budgets—we benchmark against the same local LM running on enterprise accelerators.

To answer these questions systematically, we introduce a new metric: intelligence-per-watt—a metric that quantifies how effectively inference systems convert energy into useful computation. IPW uses accuracy as a proxy for intelligence and measures task performance relative to power consumption. While accuracy is an imperfect proxy for model capabilities, it provides a standardized way to compare inference efficiency across different model-hardware configurations.

IPW = (mean accuracy across tasks) / (mean power draw during inference)

Accuracy is expressed as a percentage; power draw is measured in watts (W).

A higher IPW indicates greater inference efficiency—more “intelligence” delivered per watt of power consumed. We measure IPW by: (1) evaluating each model on diverse tasks to compute mean accuracy, (2) measuring power draw while processing each query, then averaging these measurements across queries, and (3) computing their ratio.

❓Studying Local AI Efficiency through Intelligence-Per-Watt

Our study focuses on single-query inference (i.e., batch size = 1), allowing us to isolate intrinsic model-hardware efficiency from system-level inference time optimizations. IPW captures gains from both model architecture (e.g., achieving higher accuracy with fewer parameters) and hardware design (e.g., more compute per watt), making it well-suited for comparing various model–accelerator pairings.

To understand local AI efficiency, we conducted a large-scale empirical evaluation, benchmarking 20+ state-of-the-art local LMs across diverse hardware setups. Our dataset includes 1 million real-world queries, for which we rigorously measured both accuracy and energy usage. Below, we detail our experimental design and measurement methodology.

Study Design

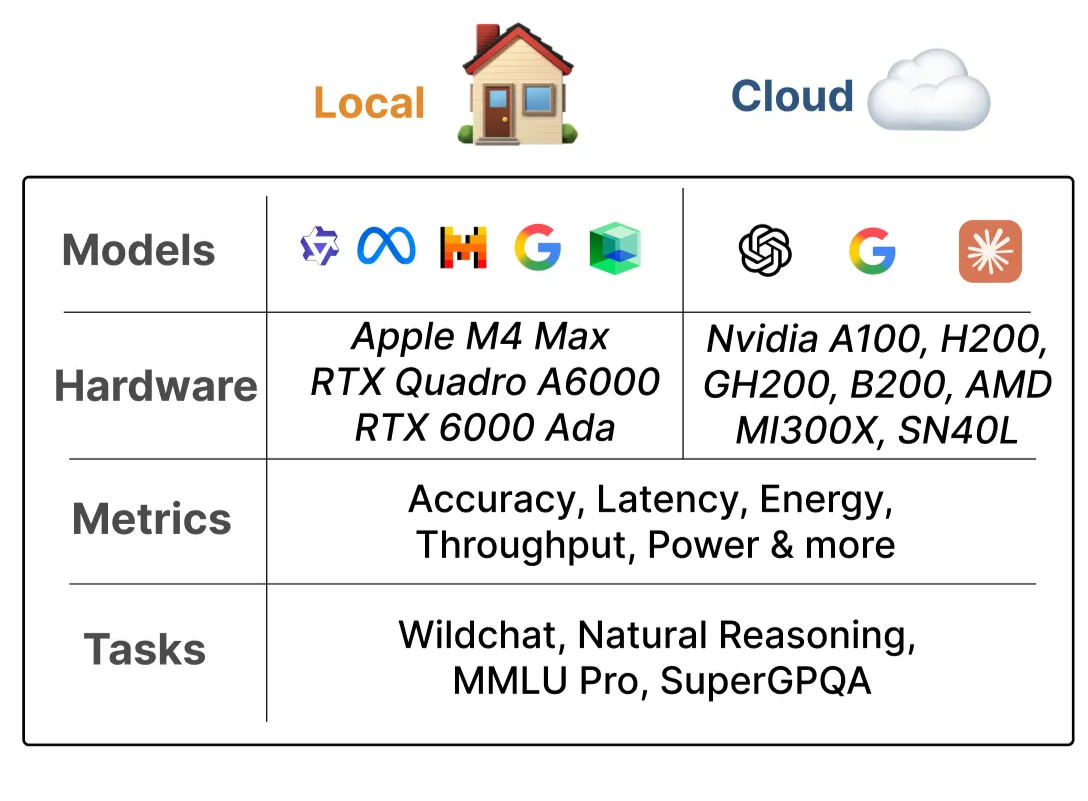

Models: 20+ state-of-the-art local LMs (Qwen3 4B-14B, gpt-oss-20b/120b, Gemma3 4B-12B, IBM Granite 4.0 1B-7B)

Hardware: 3 local accelerators from 2023-2025. To establish upper bounds on intelligence-per-watt for local LMs, we benchmark the same models on 5 enterprise-grade accelerators (2023-2025) including Nvidia, AMD and Sambanova.

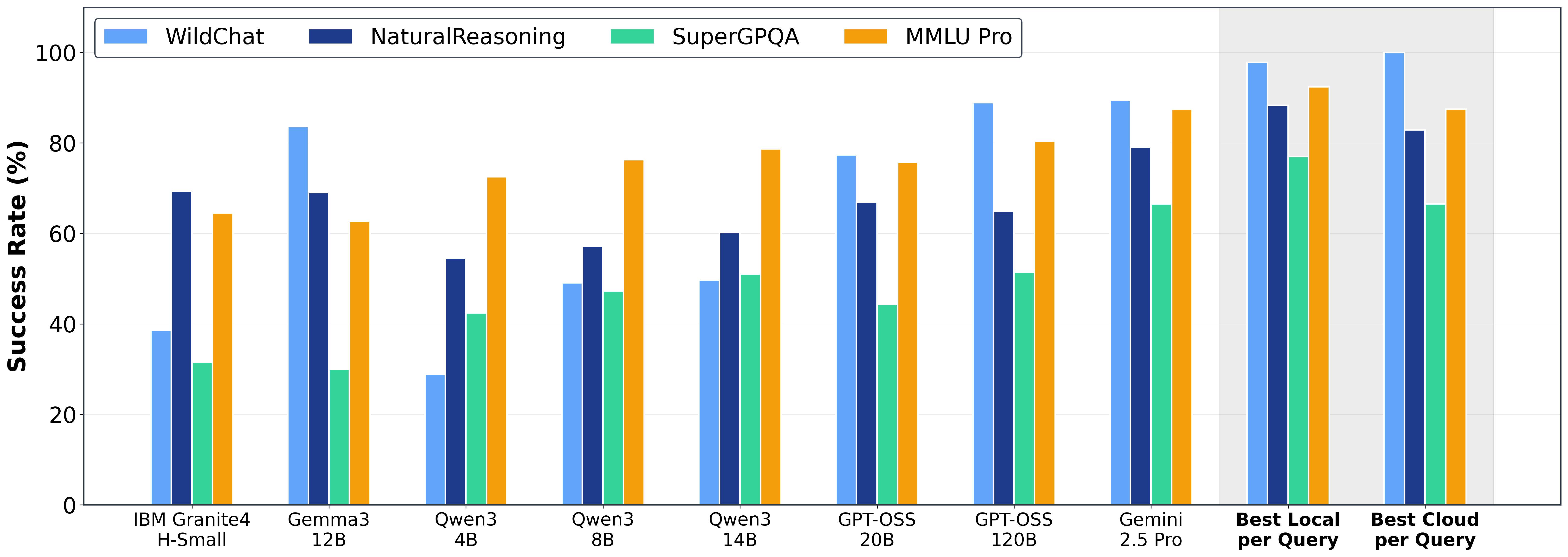

Workloads: 1M queries spanning three complementary data sources: (1) real-world ChatGPT queries (WildChat) spanning mathematics, code, and other domains that match Claude.ai's usage patterns (5 of 6 top occupational categories); (2) general reasoning tasks (Natural Reasoning); and (3) standardized benchmarks measuring knowledge breadth (MMLU-Pro) and expert-level reasoning (SuperGPQA). Our study focuses on a subset of LLM workloads: single-turn mainstream chat queries that represent a substantial portion of frontier model traffic (Deng et. al). We don't perform evaluations on agentic tool use (e.g., TauBench, TerminalBench), long-horizon planning, or long-document processing (e.g., FinanceBench) where local LMs are known to lag frontier LM performance by up to 45 percentage points. We leave this as future work.

Evaluation: We measure accuracy, energy consumption, latency, and compute under single-query inference conditions (batch size = 1), the standard deployment setting for local inference benchmarking (Hao et al.). We leave evaluations of larger batch sizes to future work.

Measurement Methodology

Energy Measurement: We follow standard energy measurement practices (Samsi et al., Fernandez et al., Wilkins et al.): querying NVML's energy counter for NVIDIA GPUs and using the powermetrics utility with power integration over time for Apple Silicon. However, software-based power measurements can introduce inaccuracies of 10-15%, with variations distributed across different hardware components due to architectural differences in workloads between CPUs, GPUs, and NPUs (Yang et al. 2023). Even hardware wattage meters may fall short for milliwatt-level precision, though our approach aligns with established practices and provides consistent relative comparisons across configurations. Compared to previous methodologies, we differ in two key aspects: (1) we sample at 50ms intervals for higher temporal resolution (compared to 100ms (Samsi et al.) or 15 seconds (Fernandez et al.)), and (2) for multi-GPU configurations, we aggregate energy counters from each GPU individually rather than extrapolating from a single device (Samsi et al.).

Accuracy Measurement: For chat queries where there is no ground truth answer we measure accuracy using LLM-as-a-judge evaluation established by Zheng et al. (2023) computing win/tie rates over frontier LMs (GPT-5 and Gemini-2.5-Pro). For reasoning and knowledge tasks where a ground truth answer exists, we use exact match to determine correctness.

🚀 Findings: Local AI is viable and improving

Our study reveals three key findings:

- Local LMs are capable and improving rapidly: Local LMs accurately respond to 88.7% of the collected single-turn chat and reasoning queries with accuracy improving 3.1× from 2023-2025. When considering the best-of-local ensemble (routing to the best local model for each query), local routing surpasses cloud routing on three of four benchmarks (see Figure 4).

- Local accelerator efficiency has room for improvement: Local IPW can be improved by at least 1.5x to match enterprise-grade accelerators. We benchmarked IPW of Qwen3-32B across 5 enterprise accelerators (2023-2025) and found that inference on the M4 Max (local) achieved 1.5x lower IPW compared to the B200 (enterprise), revealing significant efficiency headroom in local accelerators.

- Local Intelligence efficiency is improving 5.3x over two years: IPW is improving at 2.3x year-over-year, driven by 3.1x from model innovations (better architecture, pretraining, post-training, and distillation techniques) and 1.7x from hardware advances (see Figure 5).

These findings demonstrate that just as computing shifted from time-shared mainframes to personal computers, LLM inference can shift from centralized clouds to local devices—with smaller, efficient models handling a growing share of queries. Prioritizing IPW in both model design and hardware acceleration will expand the frontier of viable local inference.

✅ Limitations and Future Work

Our study is a first step towards understanding the viability of offloading portions of frontier LM traffic to local compute. We see several important directions for future work:

- Task Coverage: Our study focuses on mainstream chat and reasoning queries. It does not yet include complex or specialized workloads such as long-horizon agentic tasks (e.g., tool use, web navigation) or enterprise use cases (i.e., customer support management). Future iterations will expand the study to account for a full range of LLM deployment scenarios including tasks such as Snorkel Finance and Snorkel Underwriting.

- Hardware Diversity: While we profile a large subset of hardware backends, we aim to extend support to a broader range of local accelerators — including more NPUs, desktop laptops (Nvidia DGX Spark), and cell phones.

- Intelligence Efficiency in the Cloud: Our work focuses on local inference efficiency. A natural extension is measuring intelligence-per-watt for cloud-scale deployments.

- Systems-Level Inference Optimizations: We evaluate the local model and accelerator as integrated components in a single-query setting. Future work will expand IPW to isolate the contribution of individual sub-components of models and accelerators respectively on intelligence efficiency:

- Local LM —> Architecture, Pretraining, Post-training, Distillation, etc.

- Local Accelerator —> Systems Architecture, Inference Kernels, Quantization Efficiency, Attention Variations, etc.

🚀 Towards Intelligence Efficiency

We're witnessing a fundamental shift from centralized "mainframe era" inference to distributed "PC era" inference. Local LMs running on local accelerators can accurately answer 88.7% of single-turn chat and reasoning queries—a meaningful subset of total LLM workloads. Intelligence efficiency has improved by 5.3x over the past two years, with local LMs achieving 3.1× accuracy gains and local accelerator efficiency improving 1.7× with substantial headroom for optimization.

The path forward is clear: intelligence per watt should be one of the north star metrics for both model architecture and hardware accelerator design. Just as performance-per-watt guided the mainframe-to-PC transition, intelligence-per-watt will guide AI's transition to the edge—expanding the frontier of queries we can redistribute from data centers to local devices.

To accelerate this transition, we release a hardware-agnostic profiling harness (Nvidia, AMD, Apple Silicon) for measuring intelligence efficiency across model-accelerator configurations. By establishing a standardized measurement framework, developers can systematically optimize models and hardware vendors can hill-climb on intelligence efficiency rather than raw performance alone.

- If you are a hardware developer: we’d love to collaborate in extending our profiling harness to support your new hardware accelerators!

- If you are a model developer: we’d love to study your new models and understand whether they improve intelligence-per-watt locally!

- If you are a curious human: please join our mission to improve intelligence efficiency!

🔗 Additional Links

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to the SambaNova, Ollama, SnorkelAI, and IBM for their support. We’re also grateful to Alex Atallah from OpenRouter, Sharon Zhou from AMD, and TogetherAI for generously providing compute resources and credits. Lastly, thanks to the many folks who have provided invaluable feedback on this work - Simran Arora, Kush Bhatia, Bradley Brown, Rishi Bommasani, Mayee Chen, Owen Dugan, Sabri Eyuboglu, Neel Guha, Simon Guo, Braden Hancock, Jordan Juravsky, Omar Khattab, Andy Konwinski, Jerry Liu, Kunle Olukotun, Christopher Rytting, Benjamin Spector, Shayan Talaei, and Dan Zhang.

Citations

Chatterji, A., Cunningham, T., Deming, D. J., Hitzig, Z., Ong, C., Shan, C. Y., & Wadman, K. (2025). How people use ChatGPT (NBER Working Paper No. 34255). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w34255

Deng, Y., Zhao, N., & Huang, X. (2023). Early ChatGPT user portrait through the lens of data. In 2023 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (BigData) (pp. 5581-5583). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/BigData59044.2023.10386765

Fernandez, J., Na, C., Tiwari, V., Bisk, Y., Luccioni, S., & Strubell, E. (2025). Energy considerations of large language model inference and efficiency optimizations. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2504.17674

Hao, J., Subedi, P., Ramaswamy, L., & Kim, I. K. (2023). Reaching for the sky: Maximizing deep learning inference throughput on edge devices with AI multi-tenancy. ACM Transactions on Internet Technology, 23(1), 1-33. https://doi.org/10.1145/3524570

IBM Research. (2025). Granite 4.0 language models [Computer software]. GitHub. https://github.com/ibm-granite/granite-4.0-language-models

Koomey, J., Berard, S., Sanchez, M., & Wong, H. (2010). Implications of historical trends in the electrical efficiency of computing. IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, 33(3), 46-54. https://doi.org/10.1109/MAHC.2010.28

Kumar, D., Yadav, D., & Patel, Y. (2025). gpt-oss-20b: A comprehensive deployment-centric analysis of OpenAI's open-weight mixture of experts model. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.16700

Samsi, S., Zhao, D., McDonald, J., Li, B., Michaleas, A., Jones, M., Bergeron, W., Kepner, J., Tiwari, D., & Gadepally, V. (2023). From words to watts: Benchmarking the energy costs of large language model inference. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.03003

Wilkins, G., Keshav, S., & Mortier, R. (2024). Hybrid heterogeneous clusters can lower the energy consumption of LLM inference workloads. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.00010

Yang, Z., Adamek, K., & Armour, W. (2023). Part-time Power Measurements: nvidia-smi's Lack of Attention. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2312.02741

Yang, A., Li, A., Yang, B., Zhang, B., Hui, B., Zheng, B., Yu, B., Chang, B., Zhou, C., Chen, C., Dai, D., Dang, F., Dong, F., Zhang, G., Zeng, G., Li, H., Yu, H., Yang, H., Liu, J., ... Zhu, Z. (2025). Qwen3 technical report. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.09388

Zheng, L., Chiang, W. L., Sheng, Y., Zhuang, S., Wu, Z., Zhuang, Y., Lin, Z., Li, Z., Li, D., Xing, E., Zhang, H., Gonzalez, J. E., & Stoica, I. (2023). Judging LLM-as-a-judge with MT-bench and chatbot arena. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (Vol. 36, pp. 46595-46623). Curran Associates, Inc.