Mar 4, 2025 · 10 min read

ThunderMLA: FlashMLA, Faster and Fused-er!

Code | TK Part 2 | TK Part 1 | Brr

We've been playing with some new schedulers to deal with variable length sequences. (This is a common case in LLM inference, when you're serving requests from many different users.) Like everyone else, we were really excited about DeepSeek MLA so we decided to look into it!

We're excited to introduce ThunderMLA, our response to the performance challenges of large language model inference. ThunderMLA is a completely fused "megakernel" for decode that's 20-35% faster than DeepSeek's FlashMLA on diverse workloads. It turns out some simple scheduling tricks can get you pretty far! And although this release is focused on attention decoding, we think these techniques apply much more broadly.

Please be warned: this release is more art than product, although to our surprise, people are already using it in production!

Kernel Launches Are the Natural Predator of Performance

Attention decode kernels can struggle on variable-prompt workloads. Whereas prefill usually allows for a single kernel to fill the GPU, parallelizing across batch and sequence, when decoding small batches and just a few queries at a time, one needs to use other tricks like FlashInfer to keep the GPU full, but incurs other costs in doing so. The core issue lies in the substantial overhead created by:

- Running two separate kernel launches

- Tail effects between kernel executions

- Limited batch sizes when running large reasoning models (which appear, at the present, to be the future of AI)

These constraints can severely limit performance. For intuition, consider the following decode scenario with imbalanced inputs:

- A batch of 4 prompts, of lengths [4641, 45118, 1730, 1696]

- Generating 4 new tokens (e.g., for a speculator)

- 8-way tensor parallel -- that is, 16 heads per GPU for DeepSeek R1

With 4 new tokens, FlashMLA runs in 52 us on an SXM H100, achieving just 144 TFLOPS and 1199 GB/s (out of the 939 TFLOPS / 3300 GB/s advertised by NVIDIA).

As a partial solution, we're introducing ThunderMLA, a completely fused mega-kernel that represents the first step in our broader effort to rethink CUDA programming; on the same workload, ThunderMLA runs in just 41 us, achieving 183 TFLOPs and 1520 GB/s. Check it out here!

ThunderMLA applies classical computing ideas (like job scheduling) to modern AI workloads through:

- A novel interpreter template for building megakernels

- The actual ThunderMLA megakernel

- Two simple schedulers

- Advanced timing infrastructure

ThunderKittens Templates are the Natural Predator of Kernel Launches

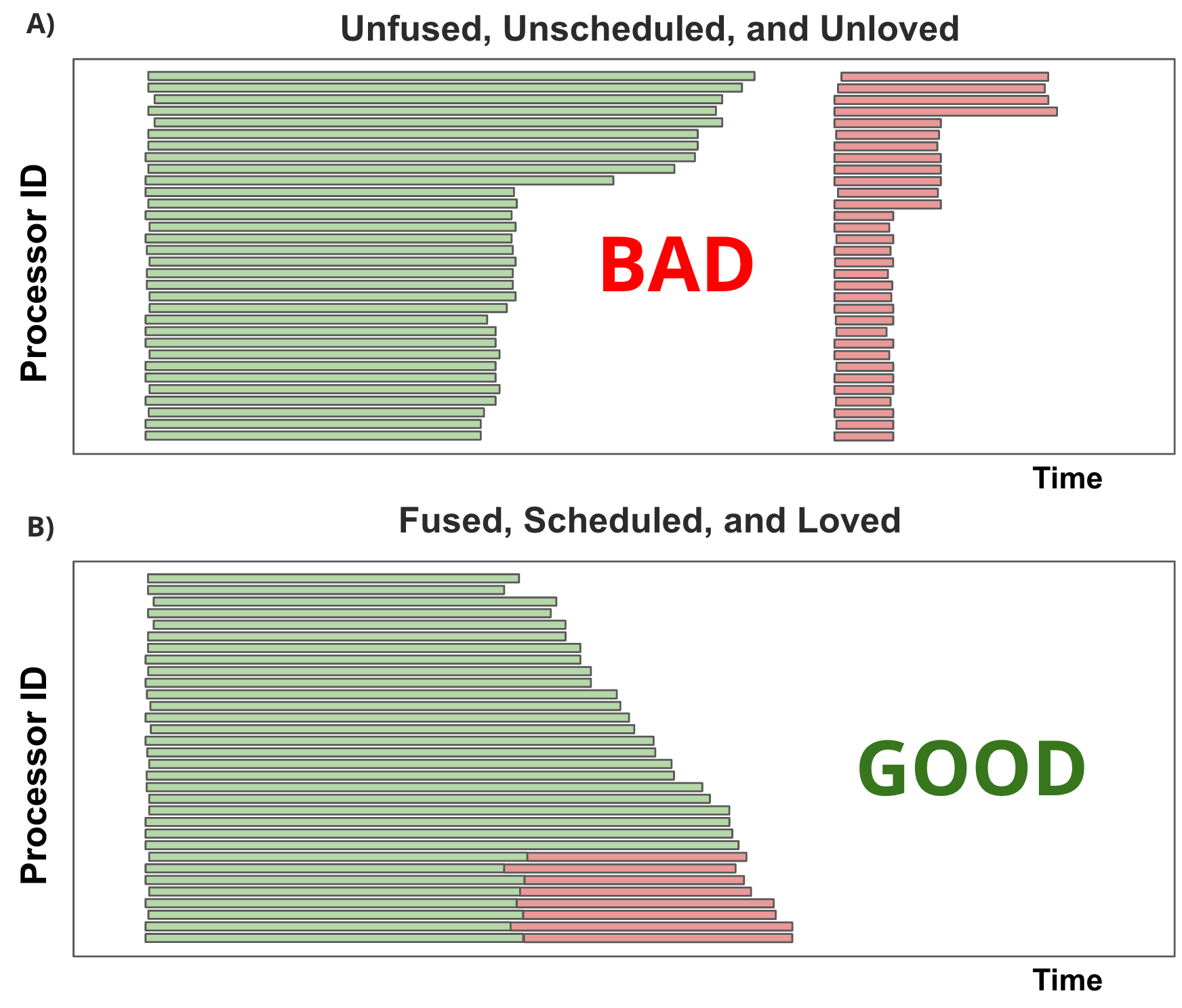

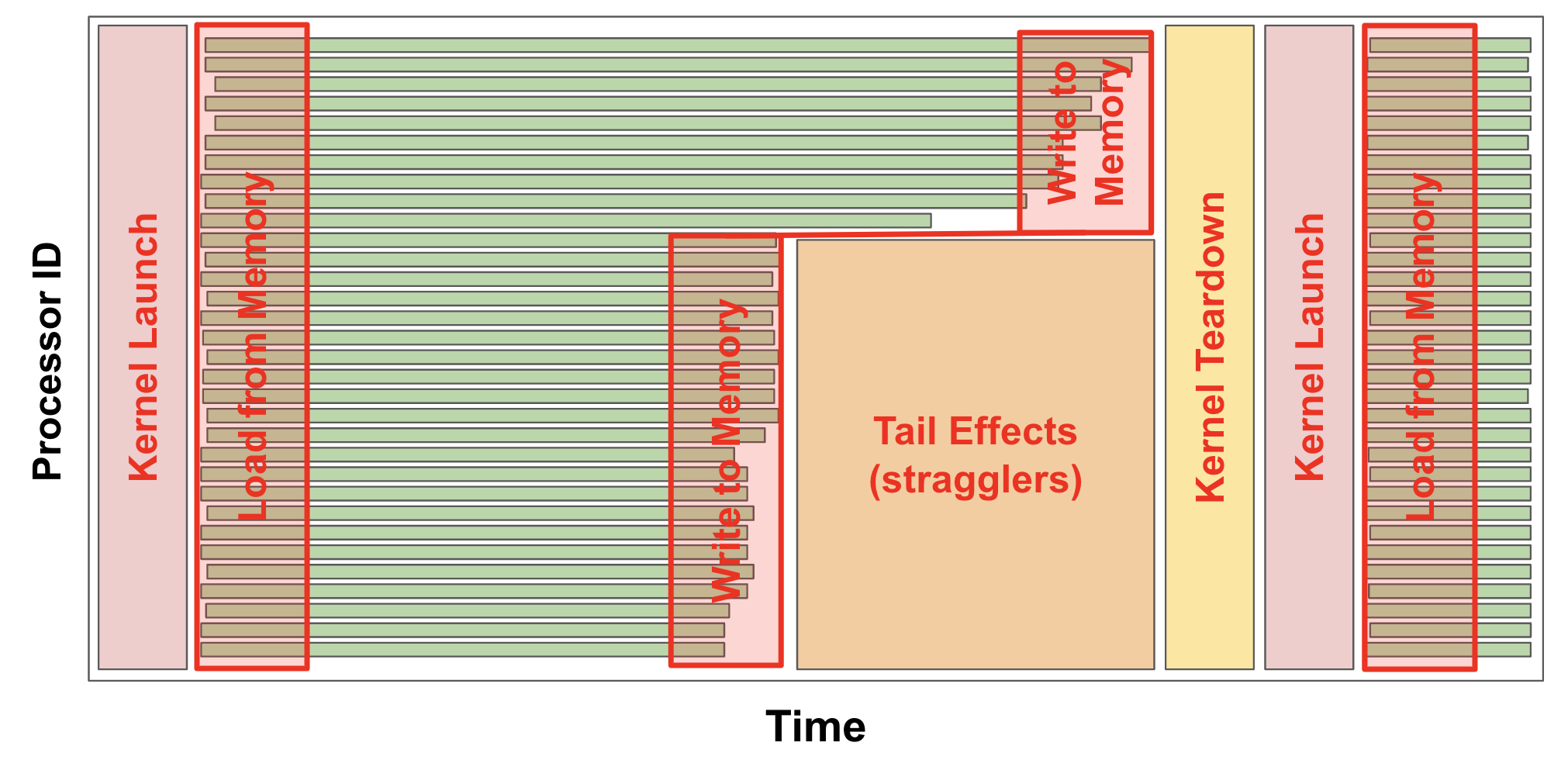

Traditionally, GPU workloads are written as sequences of kernels that exchange data through global memory (L2 cache or HBM). While this approach allows kernels to be reused, it introduces significant overhead, illustrated in Figure 1:

- Kernels must be set up and torn down; each of these can consume several microseconds

- Single-wave tail effects can often be substantial in these small-batch, fast-decoding scenarios

- Using multiple kernels prevents data reuse, thereby increasing memory bandwidth required by the GPU

Our solution eliminates these kernel launches by creating a simple virtual instruction set on the GPU. Instead of launching separate kernels, we fuse them into a single "megakernel," and then pass this megakernel its instructions at runtime through an instruction tensor, which in turn can dramatically modify its behavior. Within the megakernel, GPU SMs read from this instruction tensor, decide what work to perform next, and then execute it. Although we're initially focused on these megakernels for attention decoding scenarios, we think they're an important idea in general -- stay tuned!

We've implemented this through an interpreter template within ThunderKittens, allowing arbitrary simple kernels to be plugged together into a megakernel, each with its own opcode and instructions. Key benefits include:

- Vastly simplified pipelining within instructions, across loop boundaries

- Asynchronous fetching of the future instructions, minimizing instruction overhead

- Deep pipelines that hide data fetch latencies within and across instructions

Our implementation adapts a slot attention kernel and token reduction kernel into this interpreter template with just a few hundred lines of device code, and uses a global tensor as a semaphore to synchronize dependencies across instructions. Once both the two constituent kernels ("partial" and "reduction") of the megakernel for FlashMLA are implemented, the megakernel can be instantiated as interpreter::kernel<config, partial_template, reduction_template>. Altogether, this fused megakernel is just 250 lines of device code in ThunderKittens.

The results speak for themselves. In realistic scenarios, our Thunder MLA can be 20-35% faster than the corresponding FlashMLA implementation released by DeepSeek. On the representative workload above, ThunderMLA runs in just 41 us, achieving 183 TFLOPs and 1520 GB/s.

Here's a few other workloads we've tested with different batch sizes, KV sequence lengths, and Q tokens:

| Kernel | B 1, Seq 64k, Q 1 | B 64, Seq 256-1024 (random), Q 4 | B 64, Seq 512 Q 2 | B 132, Seq 4k, Q 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FlashMLA (μs, TFLOPs, GB/s) | 55.0, 42, 1378 | 47.0, 124, 1212 | 39.0, 59, 1092 | 226.0, 333, 2839 |

| ThunderMLA (μs, TFLOPs, GB/s) | 44.5, 52, 1700 | 39.5, 147, 2022 | 28.6, 80, 1489 | 210.0, 358, 3055 |

| Speedup (%) | 23.6% | 19.0% | 36.3% | 7.6% |

But How to Instruction Tensor?????

We've explored multiple approaches to scheduling work and generating the instruction tensors, which we'll provide more detail on in our upcoming technical report. If you're interested in collaborating, we'd love to know more about any interesting workloads you might have that could benefit from these megakernels; please send them here. In the mean time, here are two simple schedulers we've tested for ThunderMLA:

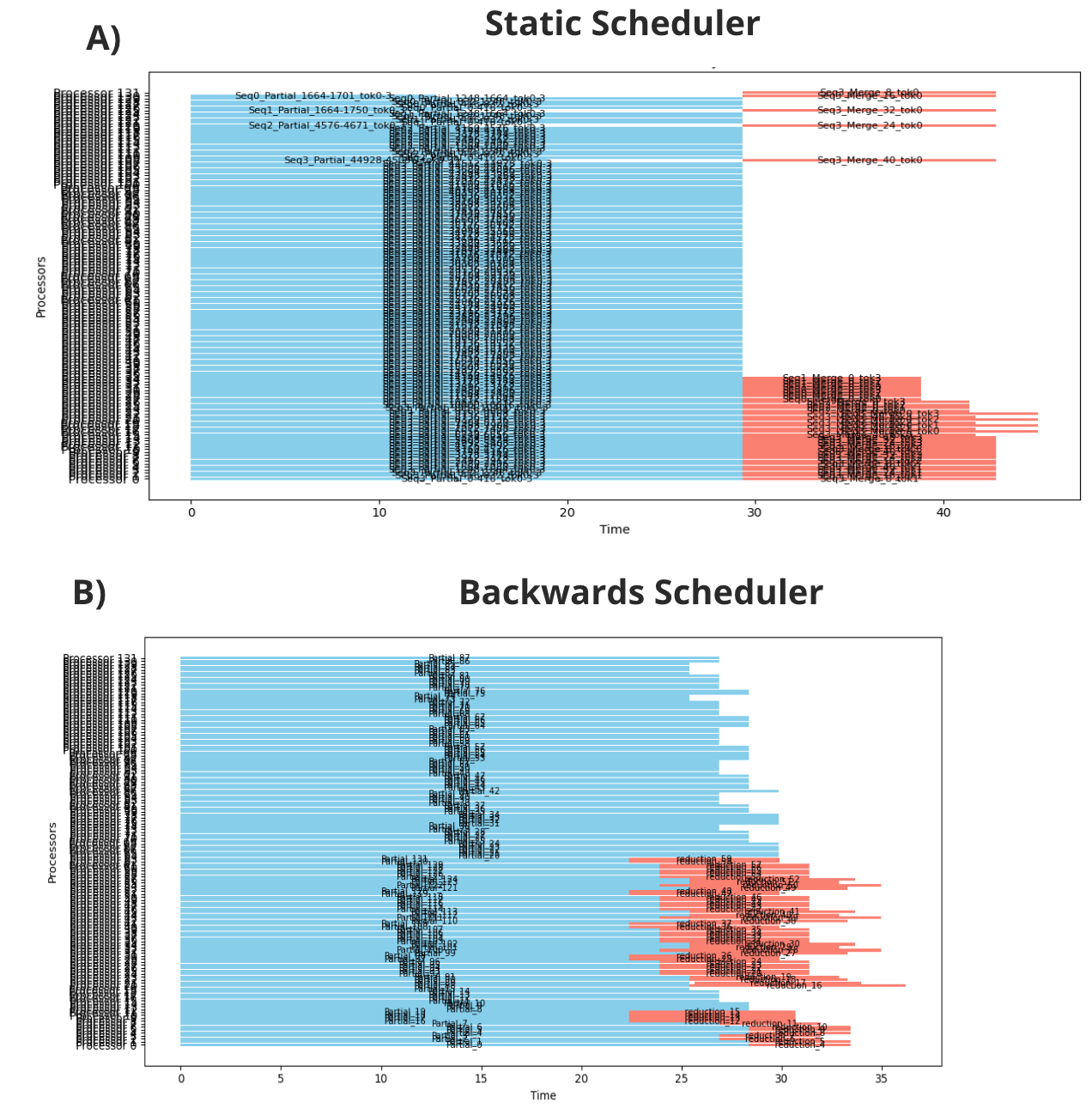

Static SchedulerOur first approach uses a simple static scheduler that:

- Divides jobs into small pieces

- Synthesizes a k-way reduction tree to merge operations

- Uses a heap-based priority queue to allocate work to available SMs

This yields good performance across various settings, though it struggles to optimally overlap reduction and compute because it doesn't consider task timing when creating instructions. An example of a proposed schedule from the static scheduler can be seen in figure 2A.

Makespan Backwards SchedulerOur second, more advanced scheduler improves performance by optimizing the makespan more aggressively:

- We know the very last event of the kernel is a single reduction task for each token, so we can work backwards from it

- We then run heuristic rollouts to determine optimal execution path

- Assigns processor IDs to each task

Taken together, this can shave an additional 10% off execution time, as visualized in figure 2B.

Note that while these schedulers are currently slower than the kernel itself (currently requiring 1-2ms), this approach remains viable because:

- Schedules can be reused across dozens of layers on large models

- Generation can happen asynchronously on the CPU while previous batches are running

- Schedules between similar batch sizes change infrequently (e.g., a batch size of 4 only needs schedule regeneration at most every 8 forward passes on average)

- Even when schedules change, they usually change in simple enough ways that a simple update is possible

Profiling MegaKernels Requires New Tools, but Good Thing We Thought of That Too

During development, we realized that NVIDIA's tools are increasingly inadequate for understanding the performance of heterogeneous and dataflow-driven kernels. NCU, while an excellent tool we love very much, isn't as well-suited for analyzing these kernels where hardware resources are more constraining than thread execution.

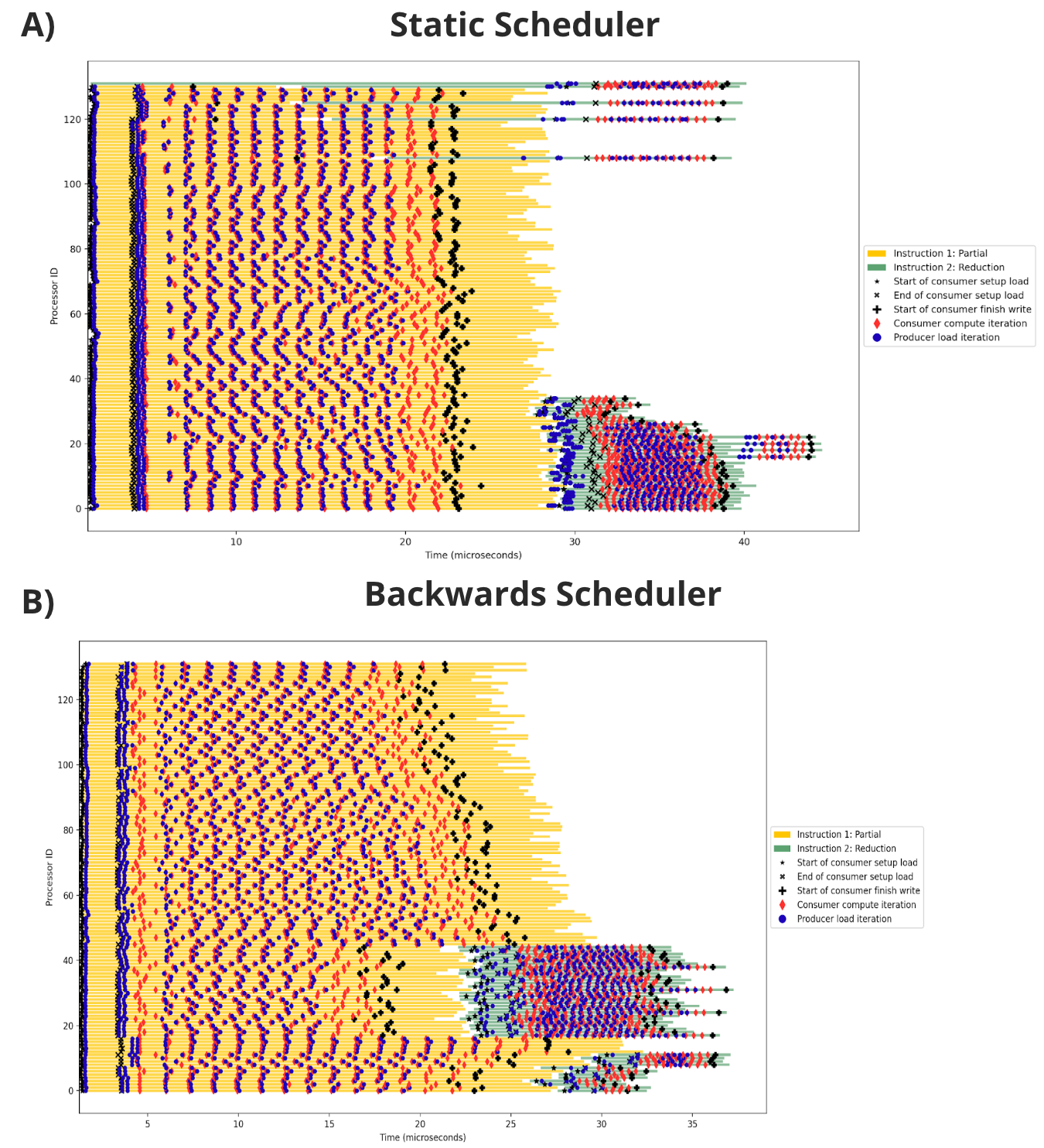

To address this, we've developed custom timing infrastructure that produces detailed Gantt charts of kernel execution, tracking events such as:

- Consumer setup phases

- Producer load and consumer compute phases

- Synchronization delays in the production tree

These tools have already proven invaluable for improving our kernels, infrastructure, and schedulers. Our infrastructure embeds a pipeline for writing out timing data, to ensure that overhead is minimal. For example, these visualizations have made it easy to understand data pipeline formation, and to track and eliminate latencies that otherwise plague these kernels. To illustrate, figure 3 has the measured performance of each of the schedules shown in the previous section:

As a simple example, one optimization that these traces enabled was to remove approximately 2 us of kernel latency from the partial operations by delaying filling the second and third stages of the three-stage KV cache pipeline until after the Q matrix is loaded -- otherwise, the out-of-order loads can further delay the compute phase from beginning. These sorts of optimizations have been very difficult to otherwise identify.

What Next?????

While we've focused on MLA with this release, these techniques apply equally well to:

- Standard multi-headed attention and grouped query attention

- Overlapping compute and NCCL communication in tensor parallel

- Other AI workloads (e.g., overlapping router and expert phases in mixture-of-experts models)

We plan to continue improving pipelining across instruction boundaries, which remains an important source of overhead (though still less than kernel launches). A full iterator model, inspired by traditional database theory, would be a promising next step.

Ultimately, we're excited about further virtualizing NVIDIA's programming model into a cleaner, more performant set of abstractions. We are convinced dataflow is the appropriate paradigm for modern AI workloads, and we aim to apply the full arsenal of classical solutions—parallel job scheduling, latency hiding, asymmetric memory costs—to these increasingly important problems.