Nov 28, 2025 · 11 min read

Stuffing MLPs Full of Facts 🧠: A Generative Approach to Factual Recall

Owen Dugan*, Roberto Garcia*, Ronny Junkins*, Jerry Liu*, Chris Ré

TL;DR

Transformers store much of their factual knowledge inside MLP layers, but how they do it is still unclear. Instead of probing trained LLMs, we take a generative approach: we explicitly construct MLPs that implement key-value fact mappings. This gives us provable guarantees of correctness, precise facts-per-parameter scaling laws, and new insights into how embedding geometry affects MLP parameter efficiency and how transformers can reliably use MLPs. Our construction is the first to be:

- General: handles realistic, non-uniform embeddings instead of idealized spherical ones.

- Efficient: matches the information-theoretic lower bound of parameters to store facts.

- Usable: can be reliably used by Transformers for factual recall tasks.

Finally, we show a proof-of-concept application of fact-storing MLPs: modular fact editing by swapping whole MLP blocks. Because the Transformer learns to cleanly use MLPs as fact stores, we can swap in an entirely new MLP block containing new facts and the Transformer immediately outputs them — no retraining required.

Full team: Owen Dugan*, Roberto Garcia*, Ronny Junkins*, Jerry Liu*, Dylan Zinsley, Sabri Eyuboglu, Atri Rudra, Chris Ré

Read the paper here!

Our in-house recipe for stuffing MLPs with factual knowledge.

Recently, we've been thinking a lot about how Transformers store and retrieve facts. Ask any LLM "What’s the capital of France?", and the answer "Paris" emerges from a tangle of weights. But the mechanisms behind fact storage are still unclear.

Most prior work takes a forensic approach: take a big pre-trained model, poke at its neurons, and try to reverse-engineer where the facts live. These works have furthered our understanding of LLM factual recall, identifying the crucial role of MLPs as key-value memories within these models.

Here, we take a different approach: can we directly construct fact-storing MLPs ourselves?

🔍 Challenges in formalizing fact storage

Before introducing our construction, we first formalize how we think about facts and summarize recent progress in the study of factual recall in language models.

Definition (Fact Set). Given key embeddings and value embeddings , a fact set is a mapping , which assigns each key a corresponding value . For example, in the "capitals" fact set, the key "France" would map to the value "Paris".

Progress on factual knowledge in LLMs. Recent works have examined how Transformers and MLPs store and retrieve large numbers of facts:

- One line of work has studied the scaling of factual knowledge in Transformers in synthetic associative recall settings. Interestingly, several works (e.g., Allen-Zhu and Li 2024, Morris et al. 2025) have found that LLMs consistently store facts at the information-theoretically optimal rate of parameters for facts.

- Nichani et al. 2024 propose an MLP construction and provide a theoretical analysis of its parameter efficiency, where their MLPs come within a polylog factor of the observed scaling of LLMs.

Prior MLP constructions make progress on understanding mechanisms for fact storage. However, these works have three major limitations:

-

Restrictive assumptions. Prior constructions assume idealized inputs and outputs (specifically, that they're uniformly spherically distributed). However, we find that these constructions fail to store facts correctly when using messy, anisotropic embeddings like the internal representations of LLMs.

-

Inefficiency. Prior constructions remain asymptotically less efficient than the information-theoretic limit: theoretically, by up to when storing facts! When implemented, they are more than less parameter efficient than gradient-descent-trained MLPs for spherically-distributed embeddings, and fail entirely for anisotropic embeddings.

-

Not evaluated within Transformers. Prior works didn't investigate whether Transformers could reliably use constructed MLPs for factual recall tasks.

Our work addresses each limitation, yielding constructions capable of handling realistic embeddings, optimally storing facts per parameter, and being usable within Transformers for factual recall:

- Generality. Our construction provably stores facts for all but a measure-zero set of feasible MLP inputs/outputs.

- Asymptotic efficiency. Under the spherical inputs/outputs setting from prior work, our MLPs match the asymptotic information-theoretic lower bound of parameters for facts. Beyond this idealized case, we show that fact-storage efficiency is governed by a single embedding-quality metric, the decodability, which quantifies how non-uniform or poorly structured embeddings reduce achievable efficiency.

- Usability. We identify a small set of architectural tweaks that enable Transformers to reliably use fact-storing MLPs for factual recall! On a synthetic factual recall task, 1-layer Transformers equipped with constructed MLPs achieve facts-per-parameter scaling comparable to the information-theoretically optimal observed in LLMs.

Roadmap

- We'll first walk through the high-level intuition behind our construction, which combines a encoder gated MLP with a linear decoder. We then show that this construction achieves facts-per-parameter scaling that matches gradient-descent-trained (GD) MLPs — unlike prior constructions — and that for general embeddings, this scaling depends on our decodability embedding-geometry metric.

- Next, we demonstrate how to make Transformers reliably use these fact-storing MLPs for factual recall. In doing so, we'll identify a tradeoff between the fact-storage capacity of an MLP and its usability by Transformers.

- Finally, we show how our insights unlock a new capability: modular fact editing in Transformers by swapping out entire MLP blocks.

🧱 Our encoder-decoder framework for constructing MLPs

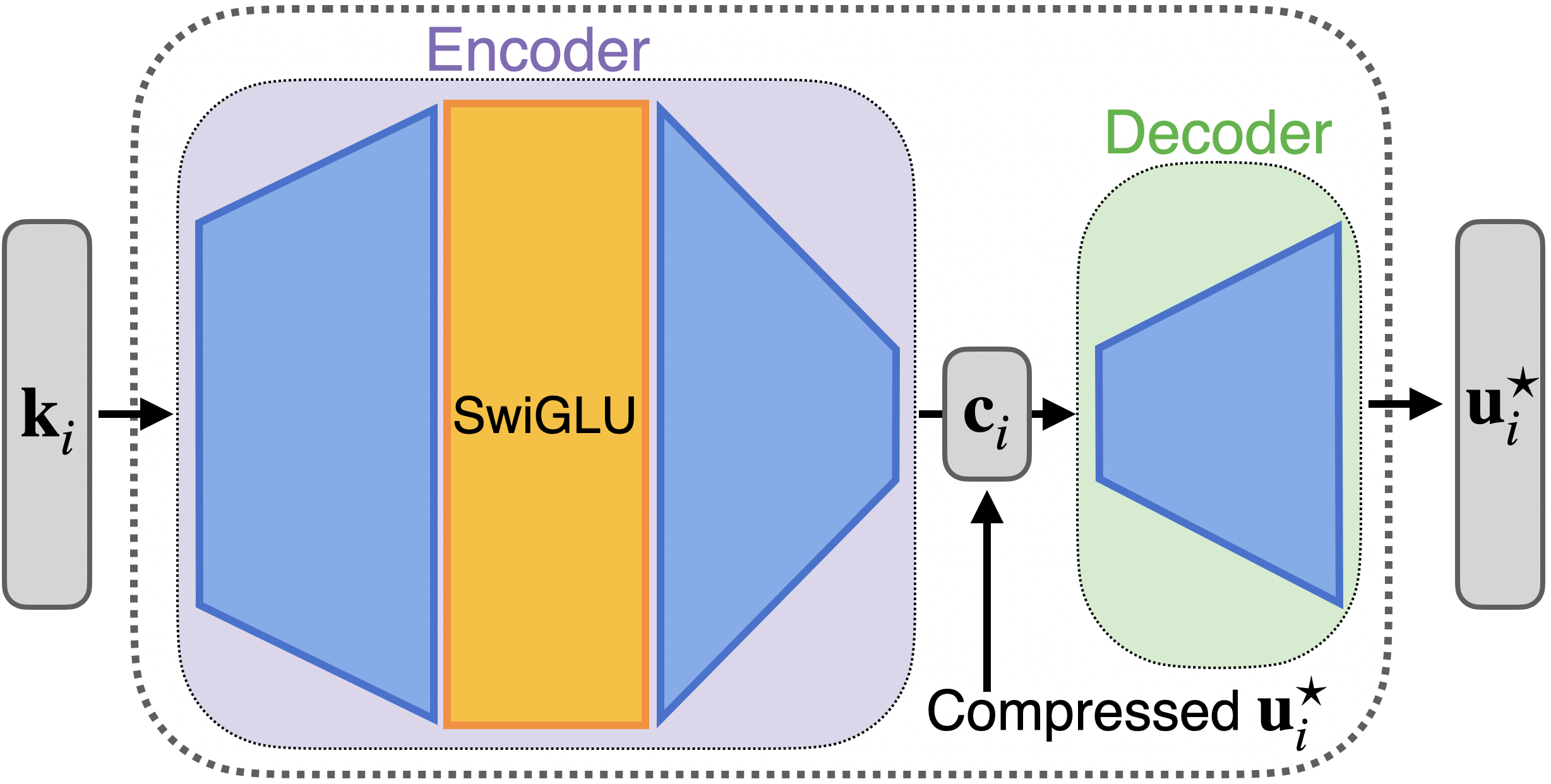

At a high level, the key insight in our construction is to decompose a single-hidden-layer MLP into two subproblems (Figure 1):

- An encoder that maps from -dimensional inputs (key embeddings) to a -dimensional compressed code. We propose a gated MLP encoder that can represent all but a measure-zero set of keys and compressed codes.

- A decoder that maps from the compressed code to -dimensional outputs (value embeddings). A simple way to produce a compressed code and its decompression method is with a random projection matrix, via a Johnson-Lindenstrauss-type argument.

Intuitively, Johnson-Lindenstrauss tells us that although the value embeddings live in , we can compress them into as few as dimensions while still distinguishing them with high probability. Introducing this -dimensional bottleneck is what makes the construction parameter-efficient: the encoder only needs to produce a short code, and the decoder only needs to ensure that the decompressed vectors approximately match the target values.

Figure 1: Our constructed MLP uses an encoder–decoder structure to achieve asymptotically optimal fact-storage capacity.

This decomposition lets us analyze the encoder and decoder separately, which in turn allows us to prove correctness and optimal fact-storage capacity. We'll explore the construction in more detail in Part 2 of the blog: stay tuned!

📏 Output geometry fundamentally limits fact-storage capacity

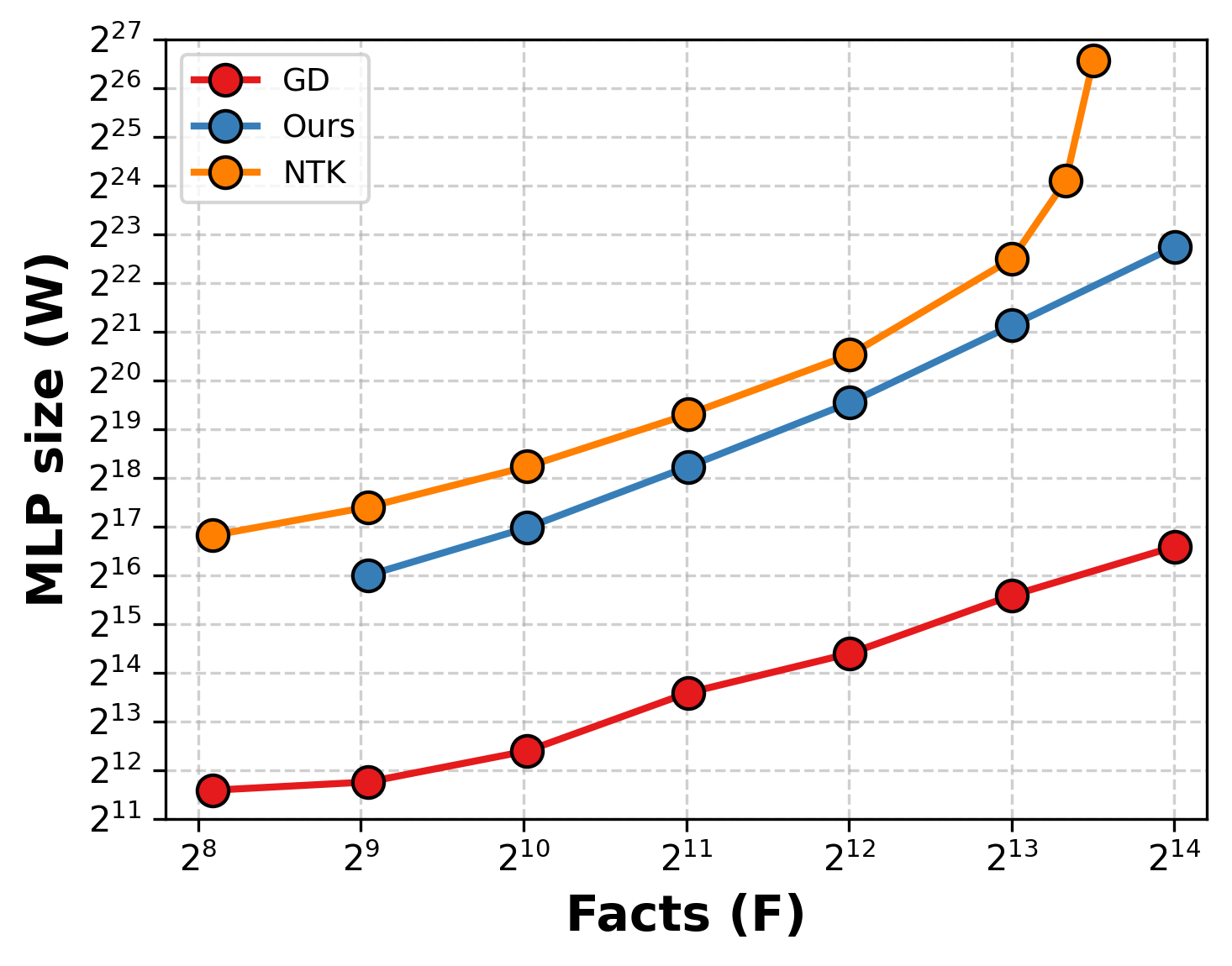

While developing the construction, we discovered a metric on the output embeddings: , the decodability. This quantity summarizes how "tightly packed" the output embeddings are, with small values indicating tightly packed embeddings (Figure 2). Surprisingly, we found that is predictive () of fact-storage capacity for both gradient-descent-trained and constructed MLPs — including ours and prior constructions!

Figure 2: Lower decodability means MLPs need more parameters to store a fixed number of facts; this holds for gradient-descent-trained (GD) MLPs, for ours, and for the construction from (Nichani et al. 2024) (NTK).

📈 Our construction achieves asymptotically optimal scaling

We find that this simple encoder-decoder framework is enough to asymptotically match the facts-per-parameter scaling of gradient-descent-trained MLPs (Figure 3). In contrast, prior constructions (NTK) exhibit asymptotically worse scaling as more facts are packed into a fixed dimension.

Figure 3: Our MLP construction is the first to match the asymptotic scaling of GD MLPs.

🛠️ Transformers learn to use our constructed MLPs

Now that we know how to construct MLPs to store facts, can a Transformer actually use those fact-storing MLPs for factual recall tasks?

Excitingly, the answer is yes — but only after a few architectural tweaks to ensure the Transformer is reading the MLP’s facts rather than memorizing them itself.

Changes we needed to make for Transformers to interface with fact-storing MLPs:

- Tying MLP and Transformer embeddings and freezing the pre-MLP RMSNorm. Ensures keys and values remain in the embedding geometry the MLP expects.

- Removing residual connections. Forces information to flow through the MLP instead of bypassing it.

- Freezing value and out-projection matrices to identity. Prevents the attention parameters from being used as an alternative fact store.

We expect these constraints can be relaxed; exploring this is promising future work!

To evaluate these modifications, we define a Synthetic Sequential Factual Recall (SSFR) task. Crucially, we needed a controlled setting that measures whether the Transformer is actually extracting facts from the MLP instead of storing them in its own parameters.

In this setting, we find that a 1-layer Transformer can achieve >99% factual recall while matching the facts-per-parameter scaling exhibited by LLMs (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Fact-storing MLPs are usable within Transformers. Transformers equipped with our constructed MLPs exhibit scaling that closely matches the fact-storage capacity of MLPs in isolation.

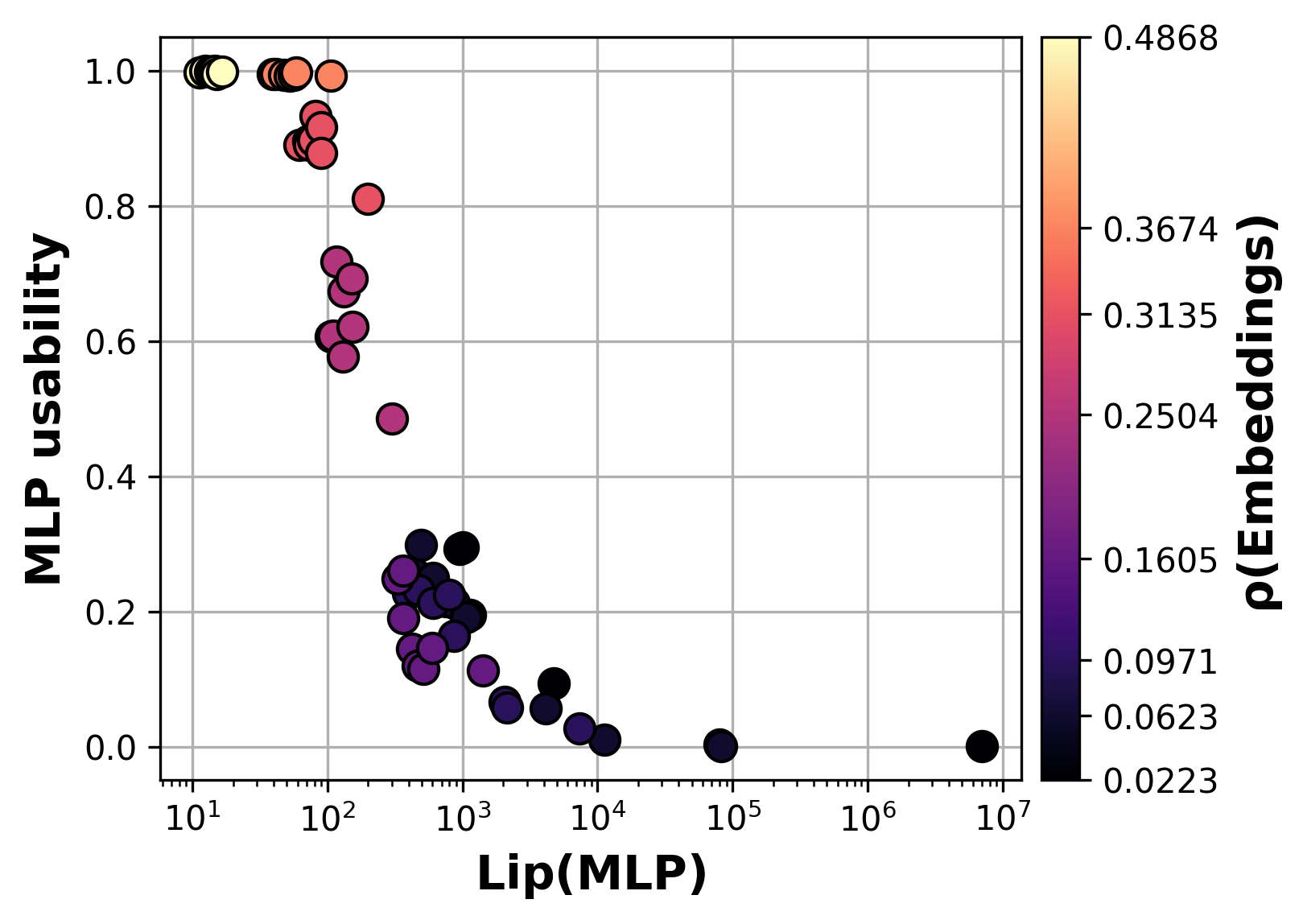

⚖️ The capacity-usability tradeoff

Along the way, we uncovered a fundamental tension between the number of facts an MLP stores (its capacity) and how readily Transformers can access that MLP's facts (its usability). Building off our insight about embedding decodability, it's possible to increase the capacity of an MLP by manually spacing apart the output embeddings within fact-storing MLPs: we call this technique embedding whitening. Interestingly however, despite increasing MLP capacity, we found this procedure decreases MLP usability overall.

The Lipschitz constant of the MLP turns out to be a key predictor (Figure 5): embedding whitening produces MLPs that store more facts, but it also destabilizes the training of Transformers that use them.

Figure 5: MLPs with larger Lipschitz constants are less usable by Transformers.

🧪 A new unlock: modular fact editing

When used in 1-layer Transformers, fact-storing MLPs unlock an exciting new capability. As a proof-of-concept, we found we can swap a GD-trained fact-storing MLP with another one storing a different fact set, and the transformer immediately outputs the new facts – with no extra training and almost no performance loss (less than 3% difference in cross-entropy loss on off-target tokens).

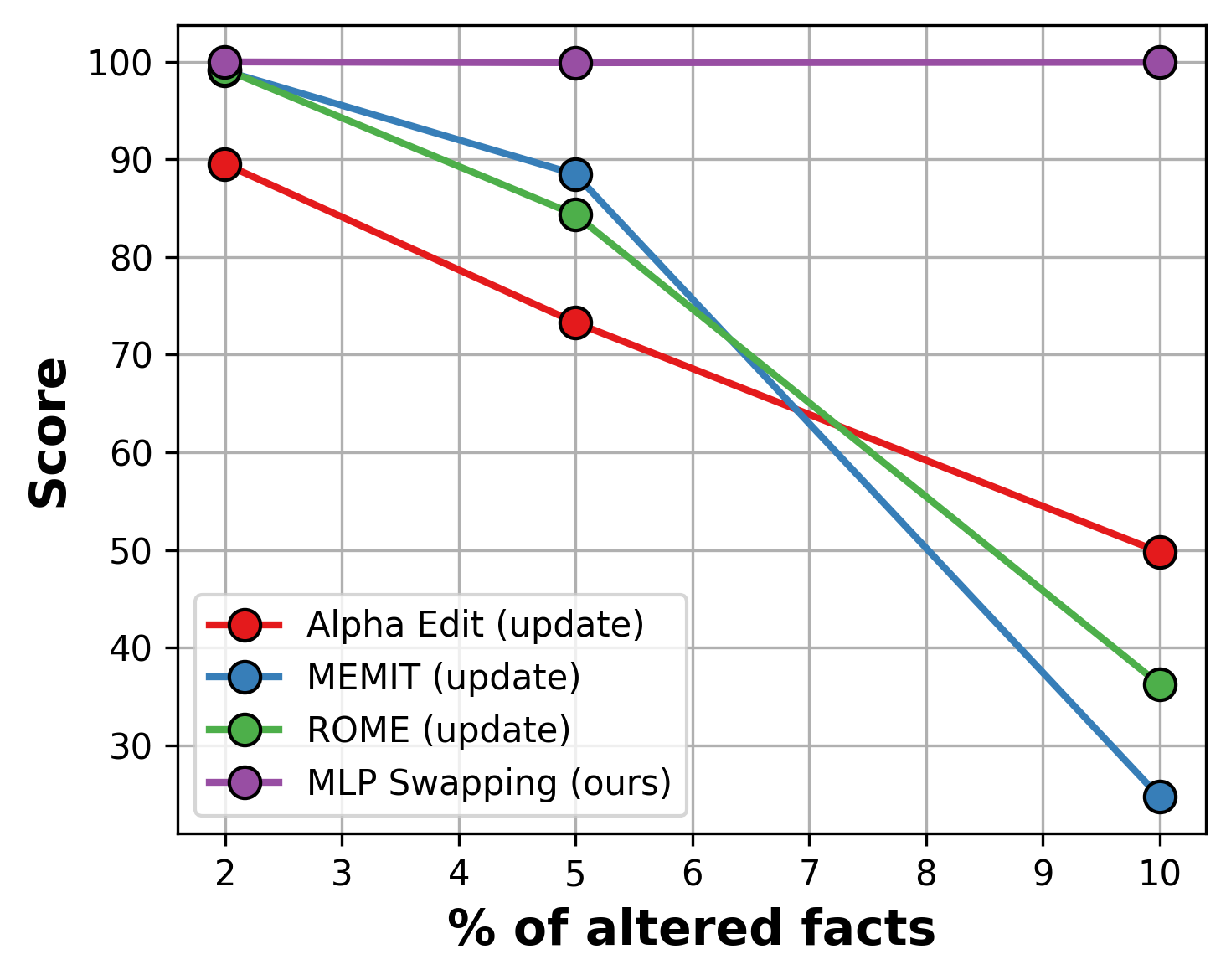

This doubles the editing score of prior state-of-the-art fact editing methods (MEMIT, ROME, AlphaEdit) when editing 10% of facts (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Transformers can use GD-trained fact-storing MLPs for modular factual recall. Swap in a new MLP, get new facts — with no additional training.

It's still incredibly early, but we're really excited about what this result hints at: memory that's truly plug-and-play. We're eager to explore how we can scale these ideas towards building LLMs whose knowledge is robust, modular, and efficiently editable.

🚀 A generative approach to understanding LLMs

We believe this work can unlock a fundamentally new way to study and understand LLMs. Instead of attempting to study pretrained models descriptively, by opening the black box of their weights and activations, why not study them constructively, by directly building systems with interpretable and provable mechanisms?

We're excited to use these tools to investigate a new suite of questions:

- Robust, adaptive memory systems. Can we design architectures whose internal memories are modular, interpretable, and support precise, localized updates?

- More efficient training and inference. Can explicit MLP constructions help us pack more knowledge into smaller models or even shortcut parts of pre-training?

- Beyond factual recall in LLMs. Can similar generative constructions shed light on higher-level LLM capabilities like reasoning or planning, or even extend beyond language to domains such as biology and physics?

If you’re interested in understanding how models store, organize, or reason with knowledge — or want to help build new mechanisms for doing so — we’d love to talk!