Nov 28, 2025 · 23 min read

Maximizing American Gross Domestic Intelligence with Hybrid Inference

Jared Dunnmon*, Avanika Narayan*, Jon Saad-Falcon*, Chris Ré.

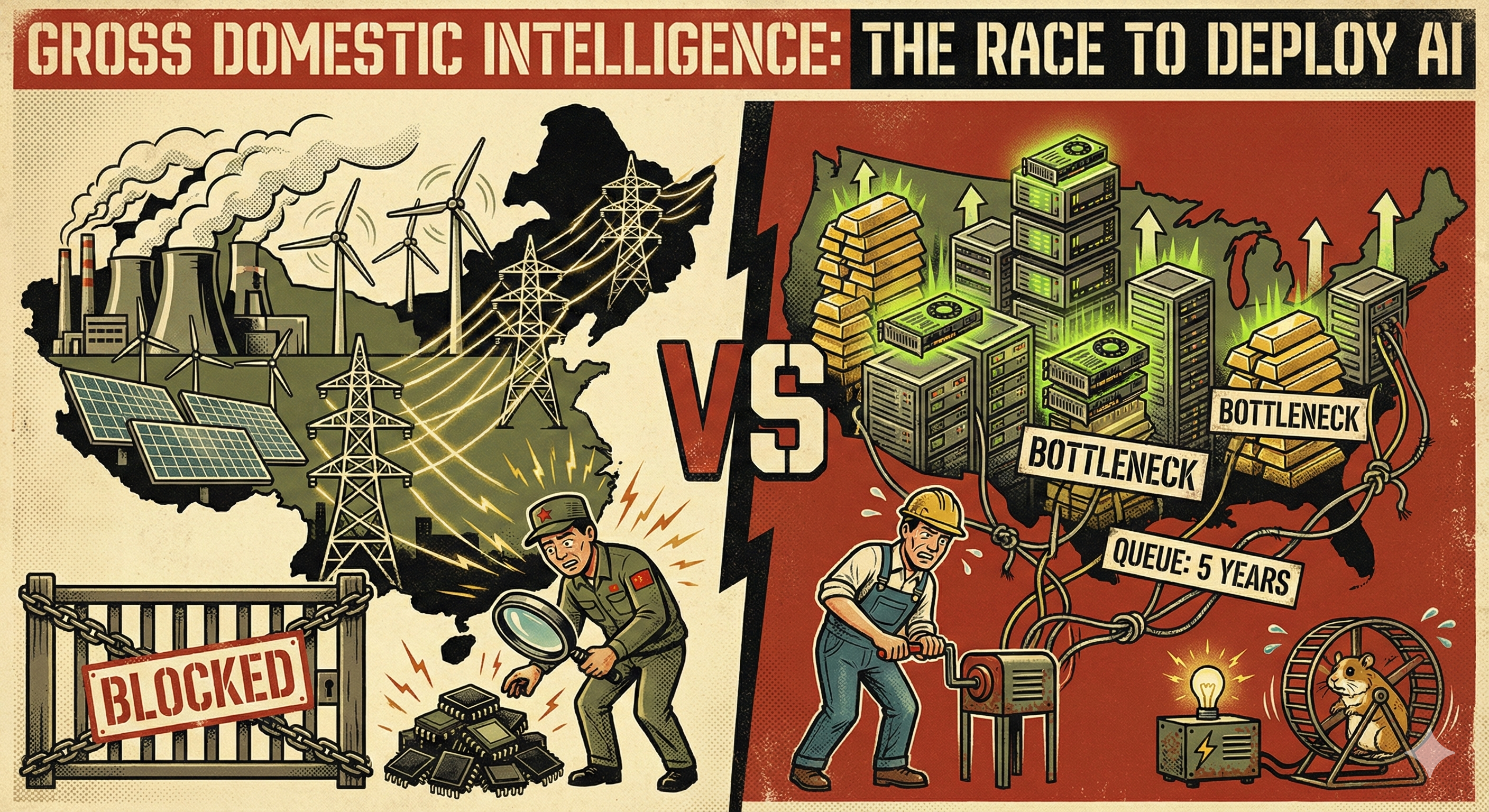

American leadership in AI has come under threat from a quiet but persistent strategy executed by the Chinese Communist Party. Locked out of high-end chips designed in the U.S. and fabricated in Taiwan with tools from American allies [2], China is making a three-way bet: a massive build-out of cheap power and grid capacity, a push to scale domestic accelerators, and aggressive use of increasingly compute-efficient open-source models. A year ago, that strategy looked almost quixotic. China's ability to train frontier-scale models was still limited relative to the U.S., and it was hard to see how pouring resources into power plants, inferior chips, and open models would win a game that seemed defined by state-of-the-art training runs.

Fast forward just a year, and it is clear the landscape has shifted. Demand for compute-intensive AI-enabled services (reasoning models, agents, etc.) is exploding, and we're entering an inference-centric phase where serving billions of queries will dominate compute demand and costs [6]. The center of gravity is moving from "Who trains the biggest model?" to "Who can run these models everywhere, all the time?" That shift changes what it means to win in AI. Victory no longer means running the biggest training job, but rather deploying the largest amount of computational intelligence to achieve scientific, economic, and military advantage.

Maximizing deployed intelligence requires two simultaneous objectives: making computation more intelligent per unit of power (better models, better chips), and maximizing the power available to run that computation. Miss either dimension and you lose: efficient models without power sit idle; abundant power without efficient computation drives up costs with diminishing returns. In this framing, the absolute amount of intelligence a nation can deploy is the product of intelligence per watt [1] and the amount of power usable for computation — what we call Gross Domestic Intelligence (GDI).

We argue that the United States should compete in AI by maximizing GDI rather than raw datacenter capacity. Viewed through this lens, one of the United States' most underappreciated competitive advantages becomes clear: because U.S.-based firms dominate operating systems, developer tools, and GPU/NPU hardware, American households and businesses own an unusually dense stock of AI-capable devices. Millions of laptops and local devices already contain AI accelerators that sit idle most of the day, and local AI models are now powerful enough to make good use of them. Activating this local compute as part of a hybrid local–cloud inference system would immediately add 30–40%1 to the nation's usable inference capacity and boost GDI by roughly 2–4×2 for single turn chat and reasoning queries, without building any new datacenters or grid infrastructure.

Introducing Gross Domestic Intelligence: A New Framework for AI Competition

To make this concrete, it helps to define terms. Think of GDI as the AI analogue of GDP: the total "intelligence output" a nation can bring to bear given its hardware, software, and energy system. At a first approximation, we can write:

GDI = IPW × min(PA, PC)

where:

- IPW (Intelligence per Watt) is how much useful model behavior you get per unit of power consumed. Higher IPW means your chips and models squeeze more intelligence out of each electron. In practice, we care about IPW at a fixed latency budget, since you can raise theoretical IPW by running cooler, slower chips—but only at the cost of much slower responses.

- PA (Power Available for computation) is how much electrical power can actually be delivered to AI workloads at the point of use. In practice it's limited by both generation capacity (how much power plants can produce) and grid capacity (transmission and distribution lines, substations, and interconnections).

- PC (Power Consumption of chips) is how much power your installed base of accelerators could draw if you ran them at 100% capacity.

The "min(PA, PC)" term reflects that the system is only as strong as the weakest resource. If you have more power than chips (PA > PC) you're compute-bound: electrons waiting around for silicon. If you have more chips than power (PC > PA) you're energy-bound: racks of GPUs you can't fully feed.

China Is Compute-Bound; America Is Energy-Bound

Seen through this GDI lens, China and the United States face inverse bottlenecks. Because of U.S.– and ally–imposed export controls on advanced accelerators and the tools needed to manufacture them, China is increasingly compute-bound: it can keep adding power plants, but it cannot easily acquire or build large fleets of high-IPW accelerators on par with Nvidia, AMD or Google's latest chips. Public U.S. estimates put Huawei's 2025 output of advanced AI chips at roughly a few hundred thousand units, far short of the millions an unconstrained ecosystem would like to deploy [11, 12].

The United States, by contrast, is increasingly energy-bound — not from lack of primary energy (it's an energy superpower) but from grid constraints on delivering electricity to datacenter sites. American firms still design the world's most capable accelerators and train the leading frontier models, but they are running into grid-side constraints: long interconnection queues, limited local substation capacity, and slow permitting for both gigawatt-scale data-center campuses and the transmission lines that would feed them [4]. Multiple planned datacenters have been cancelled due to community pushback and concerns over consumer electricity prices, with $18 billion in projects cancelled outright and another $46 billion delayed [13]. In most serious analyses today, power availability, not chips, is emerging as the single biggest bottleneck on U.S. AI data center build-outs [5].

Beyond power constraints, other structural factors — shortages of skilled labor, electrical equipment (transformers, turbine blades), and raw materials, plus the risk of tariffs and supply chain disruptions — further complicate domestic datacenter buildouts. As a result, a growing share of marginal build-out is flowing to energy-rich hubs. Gulf states leverage their freedom from green commitments, rapid infrastructure development efforts, and centralized governance to dictate terms—enabling rapid deployment of firm fossil-fuel power backed by sovereign capital—while Southeast Asian markets such as Malaysia and Indonesia compete on lower land and electricity costs.

Put back into the GDI identity, the logic is simple. In the near term, China cannot dramatically raise domestic IPW without better access to advanced manufacturing tools: while algorithmic advances (i.e., Qwen, DeepSeek) can boost intelligence, wattage is still dominated by chip- and system-level efficiency. Without leading-edge, high-efficiency accelerators, its straightforward play is to maximize PC through sheer volume — deploying massive quantities of lower-IPW accelerators — while keeping PA sky-high via its rapidly expanding power system. America, by contrast, is already saturated with high-IPW silicon but starved for new electrons, which means its unique advantage is the ability to push all three levers — IPW, PA, and PC — by continuing to improve chips, refine models, and redesign where and how AI workloads run.

The Grid-Aware Datacenter Fix—and Its Limits

An intuitive response to America's energy bottleneck is a grid-aware AI system: make datacenters flex with the grid, turning down or shifting workloads in time and space when the system is stressed. In principle, this kind of demand response could unlock significant capacity from the existing grid. By some estimates, nearly 100 GW of additional datacenter capacity could be added without breaching peak load limits if facilities reduced power draw by just 0.5% for roughly 200 hours per year [10]. AI workloads, particularly inference, are unusually well suited to this approach: unlike steel mills or residential cooling, they are one of the few major loads that can be re-routed across regions at the speed of light, shifting queries from constrained grids to areas with surplus power.

But even a perfectly grid-responsive cloud still assumes that almost every watt of inference flows through hyperscale campuses. That keeps the U.S. constrained by the slow variables of physical infrastructure: siting fights, interconnection queues, transmission build-outs, and the pace at which we can pour concrete and stack transformers. In a world where America is increasingly energy-bound rather than chip-bound, a strategy that relies solely on ever more flexible datacenters still runs into the hard limits described above.

The Untapped Asset: America's Local Accelerator Bounty

The United States has an unusually dense installed base of local AI accelerators in consumer devices, from smartphone NPUs to Apple M-series laptops. Activating this local compute as part of a hybrid inference system would immediately add 30–40% to the nation's usable inference capacity.

There is a quicker way out: treat the United States' installed base of local accelerators as a strategic asset. From smartphone NPUs to Apple's M-series laptops and emerging AI PCs, U.S. companies (i.e., Apple, AMD, Intel) already ship the chips that power the "PC AI era" [7]: local accelerators that can run models once confined to data centers within tight device power budgets. AI-capable PCs represented 14% of global shipments in Q2 2024, with the market expanding rapidly [8], and we estimate a total of 70–80M AI-accelerated PCs and Macs in the United States today3.

Critically, these chipsets are now powerful enough to run local, open source AI models that have become good enough to matter. Sub-20B-parameter "local LMs" are now surprisingly capable: in a recent study, they correctly answered 88.7% of single-turn chat and reasoning queries[1], and they already run at interactive latencies on a single high-end laptop or phone.

In terms of our simple GDI equation, lighting up the U.S. local accelerator base for inference does three useful things at the same time:

-

IPW goes up. Local chips are engineered for tight battery and thermal envelopes, and small models are now good enough to answer the majority of everyday queries. When we route those easy queries to small local models instead of always waking up a giant frontier model in the cloud, we get more "useful answers per joule" at the system level. Cloud accelerators still win on raw efficiency for the same model, but using the right-size model on an energy-conscious local chip for the bulk of traffic raises overall intelligence per watt.

-

PC goes up. PC is "how much power your installed base of accelerators could draw if you ran them flat out." Today, PC is effectively counted as "datacenter GPUs only," and the accelerators in laptops and phones are mostly idle from an AI standpoint. Turning those consumer accelerators into inference targets increases the total chip power you can, in principle, put to work for AI. National PC becomes "datacenter GPUs plus millions of client devices," — by our estimates 70-80M from AI PCs alone3 — not just whatever is inside a few hyperscale campuses.

-

PA goes up in practice. PA is "power that can actually be delivered to AI workloads," which for cloud inference is increasingly limited by siting, substation headroom, and transmission interconnections around a small number of hyperscale campuses. Local devices, by contrast, sit behind distribution infrastructure that is already built to serve homes, offices, and base stations. When a share of inference runs on those devices, it taps into spare distribution and behind-the-meter capacity that a single new datacenter cannot easily access. This does not magically increase national generation capacity, but it relieves grid and interconnection bottlenecks: more of the existing generation fleet can be used without waiting on new high-voltage interconnections. Aggregated across the country, this amounts to a large additional pool of deliverable compute power, even if not one more datacenter interconnection is approved.

By treating local accelerators as part of the national AI infrastructure, the United States can move IPW, PC, and PA together while also making its AI system more efficient, freeing up scarce training capacity, and hardening the inference layer, instead of fighting for marginal gains in datacenters alone.

How to Unlock Local Accelerators: Hybrid Inference

Local accelerators look like "free" compute sitting on every desk and in every pocket—but we can't just move all inference onto them. A meaningful slice of queries still need frontier models: they're unusually challenging reasoning tasks, or must hit strict service-level guarantees that today's small local models can't yet meet. The right architecture is therefore not "all cloud" or "all local," but a hybrid system with a router that makes one decision per query: can a small on-device model answer at the required quality and latency, or do we escalate to the datacenter? Everyday tasks stay local; only the hardest or most data-hungry queries go to the cloud.

Our Intelligence Per Watt study gives the empirical foundation for building such a hybrid system. Across 1M real-world single-turn chat and reasoning queries, we find that ensembles of local LMs running on consumer accelerators can correctly answer about >80% of single turn queries, and their IPW has improved roughly 5.3× from 2023 to 2025—3.1× from model advances and 1.7× from accelerator advances [1]. Cloud accelerators, however, still deliver at least a 1.4× IPW advantage on the same models [1]. Together, these facts define the design space: local models are now capable enough to handle most of the load, but frontier hardware remains the best place to run the tail of extremely demanding queries.

When we put these pieces together in a routing system, running over real-world traffic, a hybrid router that routes each query to the smallest capable local model — falling back to the cloud when needed — cuts energy by 64%, compute by 62%, and costs by 59% versus sending everything to the cloud [1]. As local accelerators and models continue to improve, an even larger share of queries can stay on-device, and these savings compound directly into higher Gross Domestic Intelligence.

Strategic Advantages of Hybrid Inference

Hybrid local–cloud inference delivers three distinct strategic advantages beyond maximizing Gross Domestic Intelligence:

First, it increases usable capacity and accelerates deployment. By delegating a large share of routine queries from frontier cloud models to capable local models on client devices, the U.S. can expand effective AI capacity while keeping hyperscale infrastructure focused on the hardest workloads. Because the chips and power infrastructure are already deployed—in smartphones, laptops, and desktops — a hybrid strategy can immediately raise the practical value of both PC and PA, increasing GDI by roughly 2-4x. This is a software change, not a hardware change: no interconnect queues, no construction lead times.

Second, it structurally improves both privacy and resilience. Keeping sensitive tokens and intermediate states on the device wherever possible reduces the volume of personal and mission-relevant data sent to centralized services. At the same time, distributing inference across millions of endpoints instead of concentrating it in a small number of hyperscale campuses lowers exposure to bulk data collection and single-point physical or cyber failures. In GDI terms, this makes the system less brittle with respect to localized shocks in PA (regional grid stress, datacenter outages) while maintaining a large and diverse pool of PC that can continue serving queries from unaffected devices. This matters most in environments where connectivity is intermittent or contested—from military and industrial edge operations to everyday AWS-scale cloud outages. Because local inference also reduces per-query cost, resilience effectively "pays for itself" rather than operating as a pure insurance premium: the same architectural choices that make the system harder to disrupt also make it cheaper to run.

Finally, it strengthens U.S. AI leadership abroad by exporting an American-aligned AI stack. The installed base of high-end phones and PCs already shipping with U.S.- or ally-designed application processors—paired with an emerging ecosystem of strong open-weight local models (gpt-oss, Olmo, IBM Granite, Gemma and others)—creates a natural channel for pushing American models, tooling, and norms into foreign markets. Local models that are not developed in CCP-controlled state-owned enterprises are also more likely to provide users with a genuine privacy layer, reducing how often sensitive information needs to be sent to the cloud, not just in the United States but worldwide. Because Huawei still lags Apple and AMD in efficient consumer silicon [9, 14, 15], hybrid local–cloud inference running on domestic hardware effectively exports an American-aligned AI stack: U.S. and allied chips on the device, U.S. and allied models in both local and cloud form, and an ecosystem that makes it easy for foreign users and governments to choose this stack over CCP-aligned alternatives.

Policy Levers: Making Hybrid Inference America's Default

Hybrid inference can help address the technical problem of maximizing American GDI; smart policy is what turns that design choice into a durable national advantage by shaping how much of national PA and PC actually translates into deployed intelligence.

External Policy: Export controls remain the primary tool for keeping China compute-bound. The simple GDI logic still applies: as long as the CCP can build power capacity faster than it can acquire high-IPW accelerators and advanced fab tools [3], controls on those tools are the main brake on China's ability to translate cheap energy into GDI. Maintaining and refining these controls — especially on cutting-edge accelerators and the lithography equipment needed to manufacture them — ensures that America's advantage in chip technology compounds over time.

Internal Policy: A range of policy levers can accelerate the transition to hybrid systems by making client-side inference the path of least resistance. Tax breaks for model providers who push inference to the client side, IPW standards for utility interconnection, and data privacy rules that incentivize local inference could all shift the economics in favor of distributed architectures. Procurement rules — especially in the federal government and defense ecosystem — that favor architectures defaulting to local inference when possible would further accelerate adoption. These policies work best when paired with targeted incentives for American labs to develop open-source models optimized for cloud integration, building on efforts like Llama, Gemma, Phi, gpt-oss to ensure the U.S. dominates both ends of the hybrid stack.

The Path Forward

The AI competition is entering a new phase. Victory will not be determined by who builds the most datacenters, but by who can convert energy into intelligence most efficiently.

The United States doesn't need to win a gigawatt-for-gigawatt race against China's power plant and grid expansion. Instead, it should maximize Gross Domestic Intelligence by exploiting an asymmetric advantage China cannot easily replicate: hundreds of millions of high-performance local accelerators already deployed in homes, offices, and pockets both across America and around the world combined with world-leading efficiency gains from frontier labs and continued open-source innovation. The result: American hardware everywhere, running American local models, coordinated by American frontier models on American compute infrastructure, using distributed power to bypass grid constraints and keep sensitive data beyond CCP reach.

Hybrid inference systems that redistribute workloads between local devices and cloud infrastructure can simultaneously raise all three components of GDI — intelligence per watt, chip capacity, and accessible power — while making America's AI infrastructure more resilient, privacy-preserving, and cost-effective.

The path forward is clear: maintain export controls that keep adversaries compute-bound, accelerate the shift to hybrid inference architectures, and treat local compute as critical national infrastructure. In an inference-dominated era, the nation that best leverages distributed intelligence will shape the century. America has the chips, the models, and the ecosystem to win.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Andrew Grotto, Akhil Iyer, John Hennessy, Ashray Narayan, Brad Brown, Yasa Baig, Jerry Liu, Catherine Deng and Mayee Chen for providing feedback on this draft.

References

[1] Saad-Falcon, Jon, et al. "Intelligence per Watt: Measuring Intelligence Efficiency of Local AI." arXiv, arXiv:2511.07885v2, 14 Nov. 2025, arxiv.org/abs/2511.07885.

[2] Allen, Gregory C. "Understanding the Biden Administration's Updated Export Controls." Center for Strategic and International Studies, Dec. 2024, www.csis.org/analysis/understanding-biden-administrations-updated-export-controls.

[3] "How US Export Controls Have (and Haven't) Curbed Chinese AI." AI Frontiers, 2025, ai-frontiers.org/articles/us-chip-export-controls-china-ai.

[4] U.S. Department of Energy. "DOE Releases New Report Evaluating Increase in Electricity Demand from Data Centers." Energy.gov, 20 Dec. 2024, www.energy.gov/articles/doe-releases-new-report-evaluating-increase-electricity-demand-data-centers.

[5] Green, Alastair, et al. "How Data Centers and the Energy Sector Can Sate AI's Hunger for Power." McKinsey & Company, 2024, www.mckinsey.com/industries/private-capital/our-insights/how-data-centers-and-the-energy-sector-can-sate-ais-hunger-for-power.

[6] Noffsinger, Jesse, et al. "The Cost of Compute: A $7 Trillion Race to Scale Data Centers." McKinsey & Company, 28 Apr. 2025, www.mckinsey.com/industries/technology-media-and-telecommunications/our-insights/the-cost-of-compute-a-7-trillion-dollar-race-to-scale-data-centers.

[7] Apple. "Apple Introduces M4 Pro and M4 Max." Apple Newsroom, 30 Oct. 2024, www.apple.com/newsroom/2024/10/apple-introduces-m4-pro-and-m4-max/.

[8] Dutt, Ishan. "14% of PCs Shipped Globally in Q2 2024 Were AI-Capable." Canalys Newsroom, 2024, www.canalys.com/newsroom/ai-pc-market-Q2-2024.

[9] Shilov, Anton. "Huawei's New AI CloudMatrix Cluster Beats Nvidia's GB200 by Brute Force, Uses 4X the Power." Tom's Hardware, Apr. 2025, www.tomshardware.com/tech-industry/artificial-intelligence/huaweis-new-ai-cloudmatrix-cluster-beats-nvidias-gb200-by-brute-force-uses-4x-the-power.

[10] Norris, T. H., Profeta, T., Patiño-Echeverri, D., & Cowie-Haskell, A. (2025). Rethinking load growth: Assessing the potential for integration of large flexible loads in US power systems (NI R 25-01). Nicholas Institute for Energy, Environment & Sustainability, Duke University. https://nicholasinstitute.duke.edu/publications/rethinking-load-growth

[11] SemiAnalysis. (2025, September 8). Huawei Ascend production ramp: Die banks, TSMC continued production, HBM is the bottleneck. https://semianalysis.com/2025/09/08/huawei-ascend-production-ramp/

[12] Cheng, T. F. (2025, June 13). Huawei's AI chip output limited to 200,000 in 2025, US commerce official says. South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/tech/tech-war/article/3314356/huaweis-ai-semiconductor-output-limited-200000-2025-us-commerce-official-says

[13] Data Center Watch. (2025). $64 billion of data center projects have been blocked or delayed amid local opposition. https://www.datacenterwatch.org/report

[14] Shilov, A. (2024, December 12). Huawei sticks to 7nm for latest processor as China's chip advancements stall. Tom's Hardware. https://www.tomshardware.com/tech-industry/huawei-sticks-to-7nm-for-latest-processor-as-chinas-chip-advancements-stall

[15] Shilov, A. (2025, November). Huawei's Ascend AI chip ecosystem scales up as China pushes for semiconductor independence — however, firm lags behind on efficiency and performance. Tom's Hardware. https://www.tomshardware.com/tech-industry/semiconductors/huaweis-ascend-ai-chip-ecosystem-scales

[16] Ong, I., Almahairi, A., Wu, V., Chiang, W.-L., Wu, T., Gonzalez, J. E., Kadous, M. W., & Stoica, I. (2025). RouteLLM: Learning to route LLMs with preference data. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2025). https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.18665

[17] Feng, T., Shen, Y., & You, J. (2025). GraphRouter: A graph-based router for LLM selections. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2025). https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.03834

[18] Jin, R., Shao, P., Wen, Z., Wu, J., Feng, M., Zhang, S., & Tao, J. (2025). RadialRouter: Structured representation for efficient and robust large language models routing. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.03880. https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.03880

- Our "local compute multiplier" is obtained by explicitly comparing device counts and approximate per-device throughput for datacenter accelerators and AI PCs. We assume that by around 2025 U.S. datacenters host on the order of 1.4×10⁷ H100-class accelerators, based on CSIS/SemiAnalysis estimates that U.S. labs and hyperscalers will have access to about 14.31 million AI accelerators by the end of 202 and NVIDIA documentation showing H100-class parts deliver on the order of a few thousand INT8 TOPS each (∼2,000 INT8 TOPS each). For local devices, we triangulate from NVIDIA's statement that there are already "over 100 million RTX AI PCs and workstations" in the installed base, market-research estimates that the global Mac user base is about 100.4 million with roughly 40.3% of Mac users in the United States (implying ~40 million U.S. Macs, most now on Apple silicon), and Canalys/Intel guidance that AI-capable PCs will ship in the tens of millions per year with cumulative AI PC shipments exceeding 100 million globally by the end of 2025. On conservative assumptions this yields an installed base of roughly 7×10⁷ U.S. AI-capable PCs (RTX-class Windows machines plus Apple-silicon Macs and NPU-equipped "AI PCs"), each delivering O(10²) effective INT8 TOPS for LLM inference (we use 150 TOPS as a central average), so local PCs contribute about 30–40% as much raw INT8 inference throughput as the existing U.S. datacenter fleet, implying that turning them on for inference would raise total national usable compute by roughly one-third—about a 1.3× multiplier.↩

- We compute the GDI multiplier as follows. This calculation applies to single-turn chat and reasoning queries workloads. We assume: (1) a 235B-total-parameter, 22B-active-parameter frontier model in the cloud (Qwen3-235B-A22B), (2) a 20B-total-parameter, 3.6B-active-parameter model running locally (GPT-OSS-20B), (3) local compute adds 35–40% to baseline U.S. datacenter FLOPs, (4) 88.7% of single turn chat and reasoning queries can be accurately serviced by ≤20B parameter model, and (5) account for hybrid local-cloud router accuracy ranges from 60-100% [16,17,18]. We define GDI as proportional to query throughput. In the baseline, all queries go to the cloud model, yielding throughput Qbase = C/Fbig, where C is datacenter capacity and Fbig is per-query cost. In the hybrid scenario, a router sends fraction αeff to the local model and (1 − αeff) to the cloud. Since FLOPs scale linearly with parameters, the 235B-A22B model costs ~6.1× more per query than the 20B-A3.6B model. Two capacity constraints apply: cloud capacity (1 − αeff) × Q × Fbig ≤ C; local capacity αeff × Q × Fsmall ≤ 0.35–0.40C. An oracle router achieves αoracle = 0.887; practical routers achieve αeff = a × αoracle for accuracy a ∈ [0.6, 1.0]. Solving yields Qhybrid/Qbase ≈2.1× at a = 0.6, ≈3.2× at a = 0.8, and ≈2.6× as a → 1. We report ≈3× as the central estimate; the full range is 2-4×.↩

- We approximate the U.S. installed base of “AI PCs” as follows. The U.S. has roughly 133M households, and recent ACS-based analyses suggest that about 1 in 7 lack a large-screen computer, implying that ≈86–87% of households have at least one desktop or laptop (Digitunity, citing ACS). That yields on the order of 115M PC-owning households. Allowing for more than one PC in many households plus workplace and education machines points to a total installed base of roughly 200–220M PCs and Macs in use; for shorthand we use 210M. U.S. desktop OS share data from Statcounter/Wikipedia (“Usage share of operating systems”) puts macOS at ≈28.5% of active desktop traffic, which, applied to that 210M figure, would suggest ≈60M Macs. Traffic-share tends to overstate macOS unit share, and external estimates of the global Mac base imply a lower U.S. count, so we conservatively assume that ≈40M of these are active Apple-silicon (M-series) Macs with on-device accelerators. NVIDIA reports “over 100 million RTX AI PCs and workstations” in the global installed base; combining this with a U.S. share of roughly one quarter of worldwide PC shipments (per Gartner PC shipment data) and allowing for overlap with the Mac base yields ≈20–25M RTX-class systems in the U.S. Gartner and IDC forecast tens of millions of AI PCs shipping annually, and Intel states it is on track to ship more than “100M AI PCs by the end of 2025”; scaling by U.S. share and excluding devices already counted in the RTX bucket suggests another ≈10–15M recent Intel/AMD NPU-equipped AI PCs. In shorthand: we assume ≈40M Apple-silicon Macs + ≈20–25M U.S. RTX systems + ≈10–15M additional NPU-based AI PCs, for a conservative, order-of-magnitude estimate of roughly 70–80M AI-accelerated PCs and Macs in the United States today, before counting phones, tablets, or consoles.↩