Sep 28, 2025 · 5 min read

How Many Llamas Can Dance in the Span of a Kernel?

Benjamin Spector*, Jordan Juravsky*, Stuart Sul*, Dylan Lim, Owen Dugan, Simran Arora, Chris Ré

Main Post | Code | Low-Latency Megakernels | Brr

A few months ago, we showed you could fuse an entire Llama 1B model into a single megakernel. In that system, we focused on a simple, valuable workload—batch size 1, decoding forward pass, no bells and whistles. Our goal was to demonstrate that kernel fusion could eliminate kernel launch overheads and achieve surprising speedups for low-latency cases -- and indeed, we found we could run small models around 50% faster than SOTA inference frameworks!

But other times, we want to run much larger models, in much larger batches, across 8 or more GPUs. This led us to wonder:

How much of a high-throughput workload can we fit in a single kernel?

Today, we're excited to release code for a throughput-focused, tensor-parallel, Llama-70B megakernel, and have integrated it into a state-of-the-art inference engine. In short: through software scheduling of a single kernel, we can eliminate the standard approach of coordinating between multiple kernels to meet production inference's complex requirements. Our implementation handles:

- 8-GPU tensor parallel, 16-bit inference.

- Arbitrary batch sizes.

- Mixed prefill + decode.

- Paged KV caching.

- Overlapped compute + inter-GPU communication.

- CPU-side pipelining to hide batch scheduling costs.

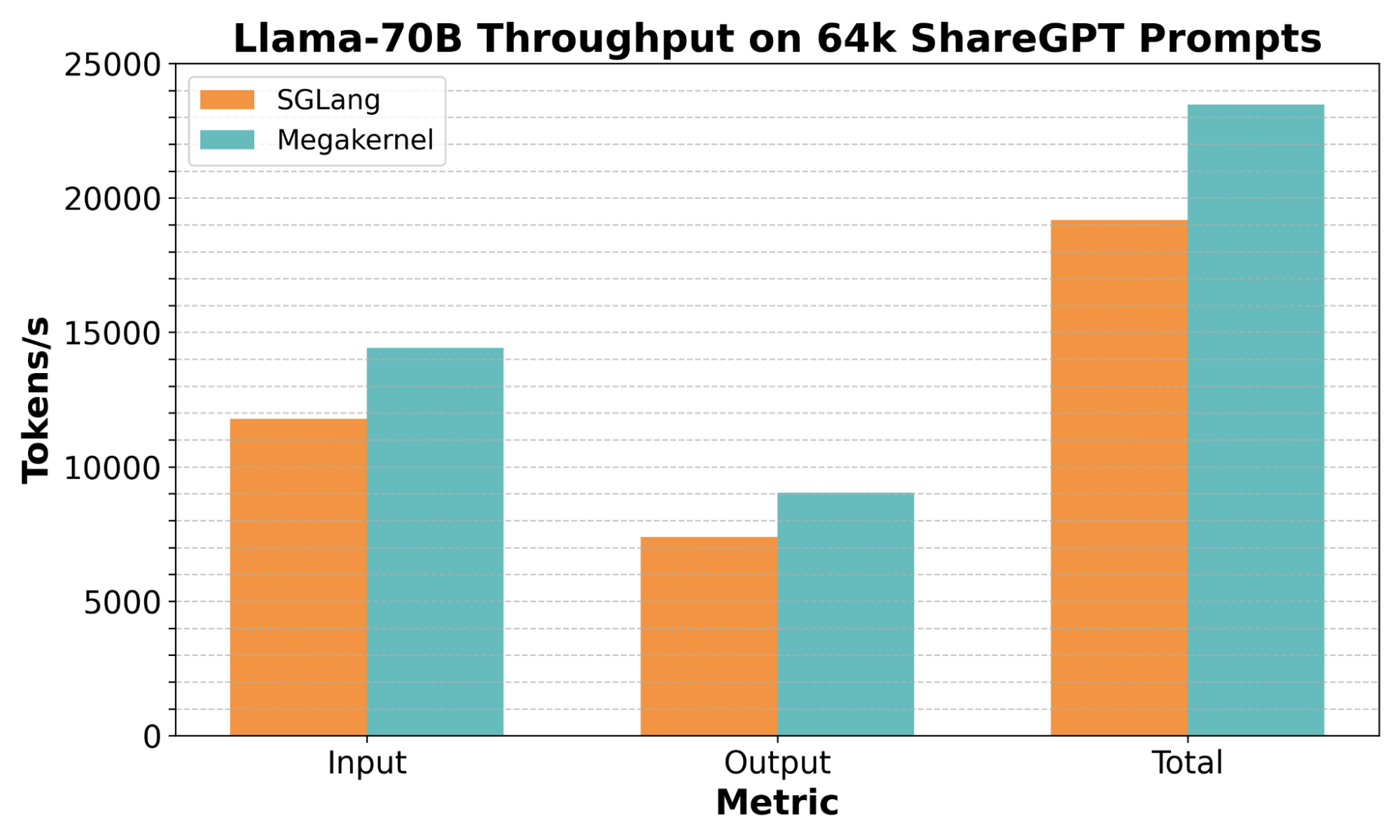

Figure 1: Speedups!

As shown in Figure 1, our prototype implementation can process 65,536 prompts from the popular ShareGPT dataset about 22% faster than SGLang, end-to-end. But the speedup isn't the main point. In our view, what's interesting is that it's possible to handle production inference's complex orchestration requirements through software scheduling of a single kernel, rather than the standard approach of coordination between kernels. We're optimistic this will open up a host of optimization opportunities for ML systems, and we're particularly excited that so much of the scheduling work can be done without expert CUDA knowledge.

Three Types of Overlapping

Production inference systems face three distinct overlapping challenges: overlapping within each SM, across different SMs, and across GPUs. Traditionally, each of these is solved by different mechanisms. In addition to its aforementioned use in low-latency decoding, we found that our megakernel framework could provide a unified approach here, too!

As with the low-latency case, our megakernel consists of an interpreter template and a set of instructions instantiated within the interpreter. Each instruction (e.g. single RMS norm, block matrix multiply) is implemented in CUDA, and the instructions are combined to define the megakernel. We generate the instruction schedule for the megakernel in advance on the CPU, and then the megakernel reads and execute these instructions. What makes this possible is that our instructions are really big, operating at the granularity of dozens of microseconds, which helps amortize the modest overhead of the interpreter. We've also worked hard to hide that overhead with warp specialization and pipelining, so that instructions transition seamlessly to the next.

Intra-SM overlapping. Traditional systems use CUDA Graphs to minimize kernel launch overhead and keep the SMs busy. You trace your computation graph once, then replay it with new inputs. In our megakernel approach, we simply eliminate all kernel launches—we explicitly schedule when each warp performs each operation, overlapping memory transfers with computation. This then frees us to implement more aggressive software pipelining within the kernel, compared to what's enabled by CUDA Graph alone.

Cross-SM overlapping. When you need producer-consumer patterns across different SMs, traditional approaches use sequential kernels, which leads to stragglers while each kernel finishes execution. Our megakernel handles this through dynamically scheduled instruction assignments. Different SMs work on different parts of the computation simultaneously, with explicit synchronization points we control, and fetch new work when they're done. This allows entire tensor-parallel GEMM, attention, and MLP operations to simultaneously coordinate without returning to the CPU.

Cross-GPU overlapping. Multi-GPU systems traditionally use CUDA streams to overlap communication with computation. While one stream runs NCCL allreduce, another processes the next layer. This requires the CPU scheduler to carefully manage dependencies and timing. In our approach, we issue remote loads and stores directly from within the kernel. This lets us interleaves fine-grained transfers to overlap them with local computation, and means the critical path never stalls on the CPU.

Why This Matters

We think that this is important for two reasons. First: it's interesting! Traditional approaches to fusion rely on compilers like XLA to merge complicated operations. In our opinion, it's fun that we can do it with a single interpreted kernel and CPU-side scheduling, and that this interpreter-based approach is enabled by the relatively large granularity of ML operations. Without this, we couldn't afford the overhead of an interpreter, and we'd need to compile in advance! We were also surprised that such a broad range of optimizations fell neatly into the megakernel approach, helping us overlap across hundreds of operations in end to end model execution.

Second, we're particularly excited by the prospect of designing more general interpreters that could be used by a wide range of model architectures and hardware platforms. In our undertaking of this work, we realized that designing these interpreters is really hard, and that more of the work ought to be offloaded to the CPU-side scheduler. In turn, a general interpreter framework would offload more decision-making to the CPU, making highly optimized systems more accessible to engineers without deep CUDA experience. And as a final bonus, it would mean that adding support for new hardware could be as simple as porting the interpreter, with the models-specific implementation and scheduler abstracted out on top.

If you're interested in reading more, we've overlapped our release of a more technical megablog.

*Work by Jordan done while at Stanford.